Crystal Clear

The entrepreneur Silvio Denz is preparing a grand celebration: Lalique’s one hundredth anniversary. A journey through the eras of glass art in Alsace. The clarity of the material fits the nature of the man.

Half an hour’s drive north of Strasbourg, at the Schwindratzheim tollbooth, the signpost knows only one direction: Paris! But France’s capital is still over five hundred kilometers away from there. Those faced with a choice between traveling to Paris and the rest of the world would be forgiven for choosing Paris. Yet, as we later learn from Silvio Denz, while you can find everything in Paris, it is not really the place to go to experience France itself. To discover the country, head for the countryside—to Alsace, the region bordering Germany. We forget Paris for the moment, leave Schwindratzheim behind, and roll straight into the Northern Vosges Regional Nature Park, en route to Wingen-sur-Moder.

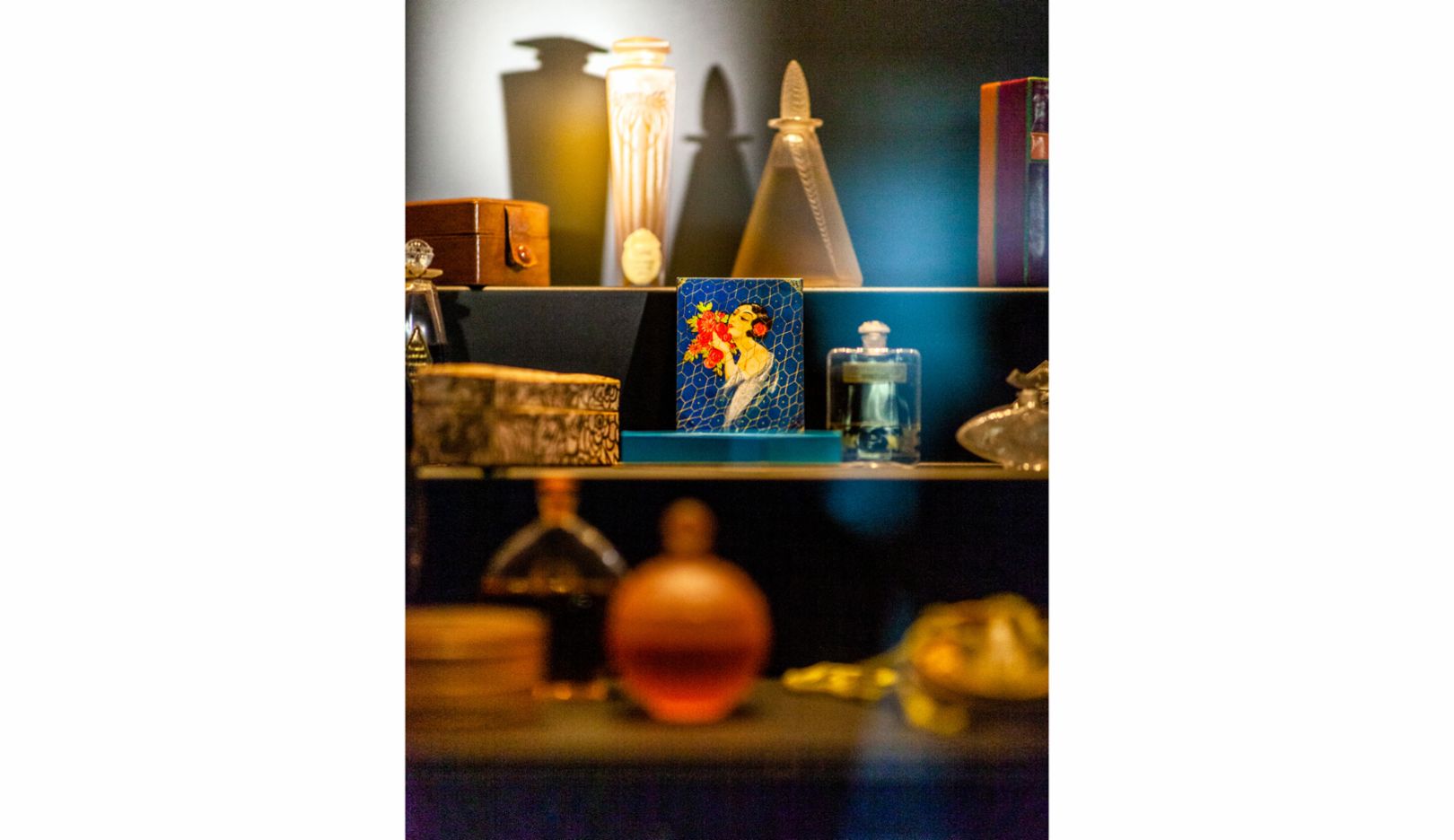

A Parisian—the jeweler, artist, and craftsman René Lalique—brought modernity and industrialization to Wingen one hundred years ago. Many decades later, the Swiss investor Silvio Denz saved the legacy of the Lalique dynasty from being sold out. He then expanded it to include new exclusive wares, opened Michelin-starred restaurants, and filled a museum with the world’s largest collection of vintage perfume bottles. He works tirelessly to make the renowned name Lalique a global brand—a label that embodies sophistication and value, design and art. “A luxury lifestyle, yes,” says Denz (64), “but not simply expensive and ostentatious. Success is defined by quality alone. The more exclusive, the better.”

With over seven hundred stores and showrooms as well as more than thirty of its own boutiques, you’ll find Lalique all around the world—from Paris, London, and Beverly Hills to Moscow, Hong Kong, Beirut, and Tashkent... and of course Wingen, in the coniferous woodland of the Vosges foothills. There, after just a few steps, we feel as if we have stepped a century back in time. Olivier Petry stands in a back room of the production facility. The clay oven builder radiates the calm of a Zen master, smoothing the surfaces of six ovens with his bare hands. “An oven lasts four months,” he says, “then it literally burns out, and I shape the next generation.”

Lalique is an artisanal operation, there’s no doubt about that. A traditional craft. In the production hall, five men walk the same short pathways time and again: between the furnace—the heart of production at 1,200 degrees Celsius—and the lehr sunk into the floor. Every few minutes Martial Rinie and his duckbill shears welcome his colleagues with the blowpipe and cuts off the red-hot vitreous body. Super-focused, high-precision work, smooth as clockwork.

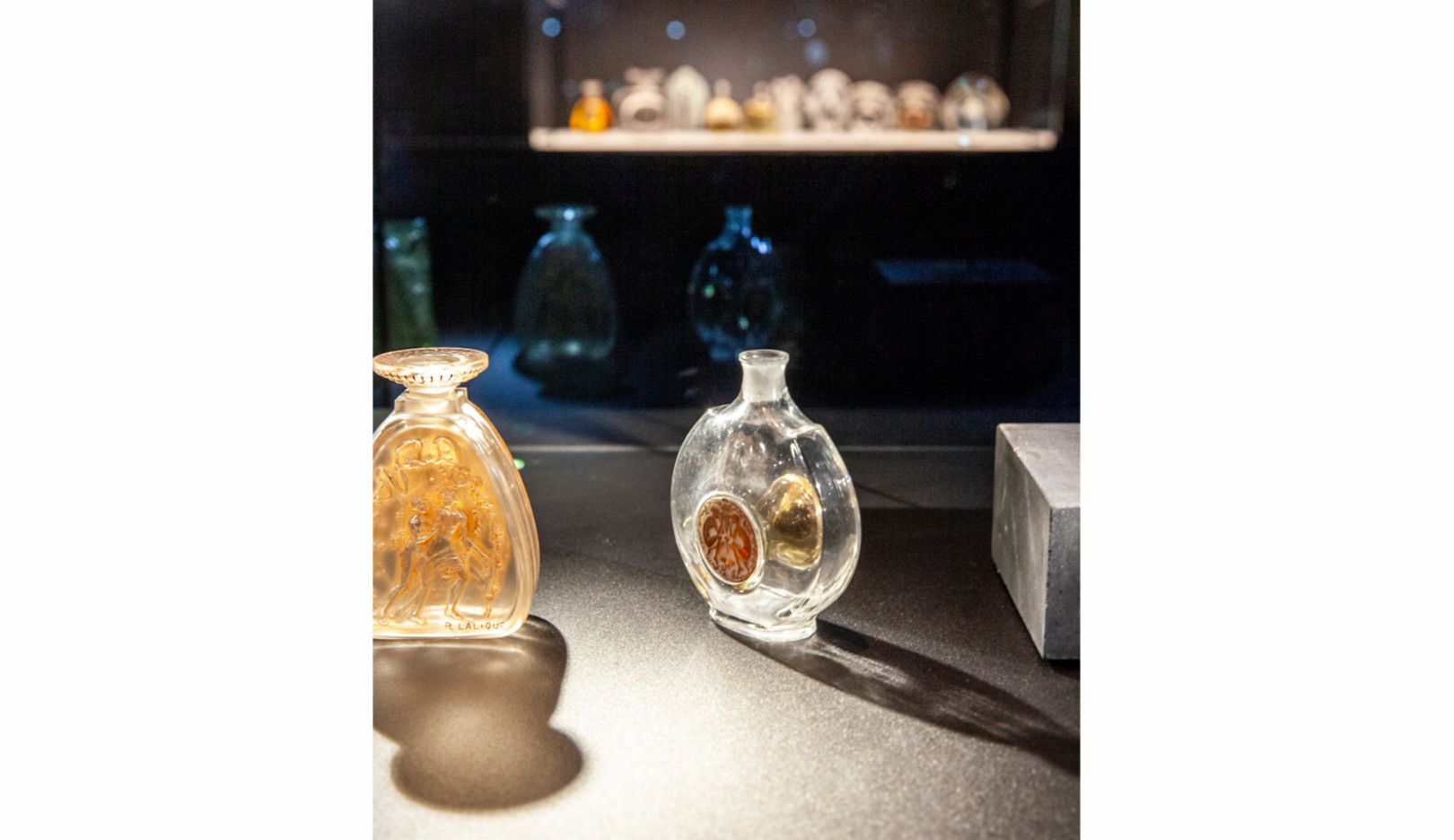

Two hundred fifty employees produce, pack, and ship more than half a million handmade, unique pieces over the course of a year. Jewelry and perfume bottles, interior design pieces and decorations such as crystal chandeliers, vases, inlays for furniture—the possibilities are limitless. Some objects require hundreds of hours of labor.

Tradition:

Silvio Denz has been driving a Porsche 911 Turbo S for twenty years, always in black. He transformed the Villa René Lalique in Wingen-sur-Moder, built in 1920, into a stylish restaurant.

Denz has invested over twenty-five million euros in the Wingen production site since 2008. Productivity has risen; but most importantly, he has significantly improved quality. “We have no desire to produce ten million units. Every piece is unique. Although some of them resemble each other, there are details in which they differ, like in a hidden object picture. We pass on our savoir-faire, our expertise, and continue the tradition.”

René Lalique once industrialized the perfume bottle. The glassworks in Alsace had plenty of work for years. When Groupe Pochet took over the Lalique family business in 1994, the Paris-based company, which specializes in cosmetics packaging, was hoping for synergies. But the future, as Silvio Denz realized a decade and a half later, did not lie in the mass production once pushed by René Lalique. It’s in exclusivity. Denz has an understated air about him. He is not one to make grand pronouncements or travel with an entourage. He makes appointments in person by phone. Direct contact is important to him. When he took over Lalique, the then director in Paris insisted on a strictly hierarchical company model with a rigid chain of command from top to bottom. It took forever for information to trickle back up to the top. When Denz introduced his cooperative management style, the director complained, “You’re undermining my authority!” Denz dismissed the entire board. “I’m a team player. I strongly believe that together we can achieve much more. I don’t care which of our 720 employees gives me information, I just want to be informed quickly and competently.”

Artisanal production:

Liquid glass from the furnace assumes fantastical shapes in artistically crafted forms. The molds are prepared with a chisel, a mallet, and great dexterity.

Over lunch at Château Hochberg in Wingen—the third gourmet venue initiated by Denz alongside the Michelin-starred restaurant Villa René Lalique and Château Lafaurie-Peyraguey in Bordeaux—the entrepreneur comes to speak about his father. The family was not poor, but not rich either. How did Denz become the successful multi-entrepreneur he is today? “My father said: ‘Languages are the doors of life. Without language, people will take advantage of you.’” Denz learned English in Milwaukee, French in Lausanne, and began a typically Swiss career as a banker at the cantonal bank in Basel. He got into a family business rather by chance—and shaped the eight-man company into the perfumery chain Alrodo with eight hundred employees. Asked what it takes to succeed, he names virtues such as good education, diligence, and hard work. Instead of courage, he says “calculated risk”—a maxim he maintains whether he’s investing in vineyards in Bordeaux or in Scotch whisky.

Lalique was in the red in 2008. Denz knew his way around the perfume business and understood immediately: “Eight million euros in perfume sales is not enough. Only if we succeed in doubling or tripling that amount can we earn money. Today we’ve quadrupled it. The perfume business is the mainstay.”

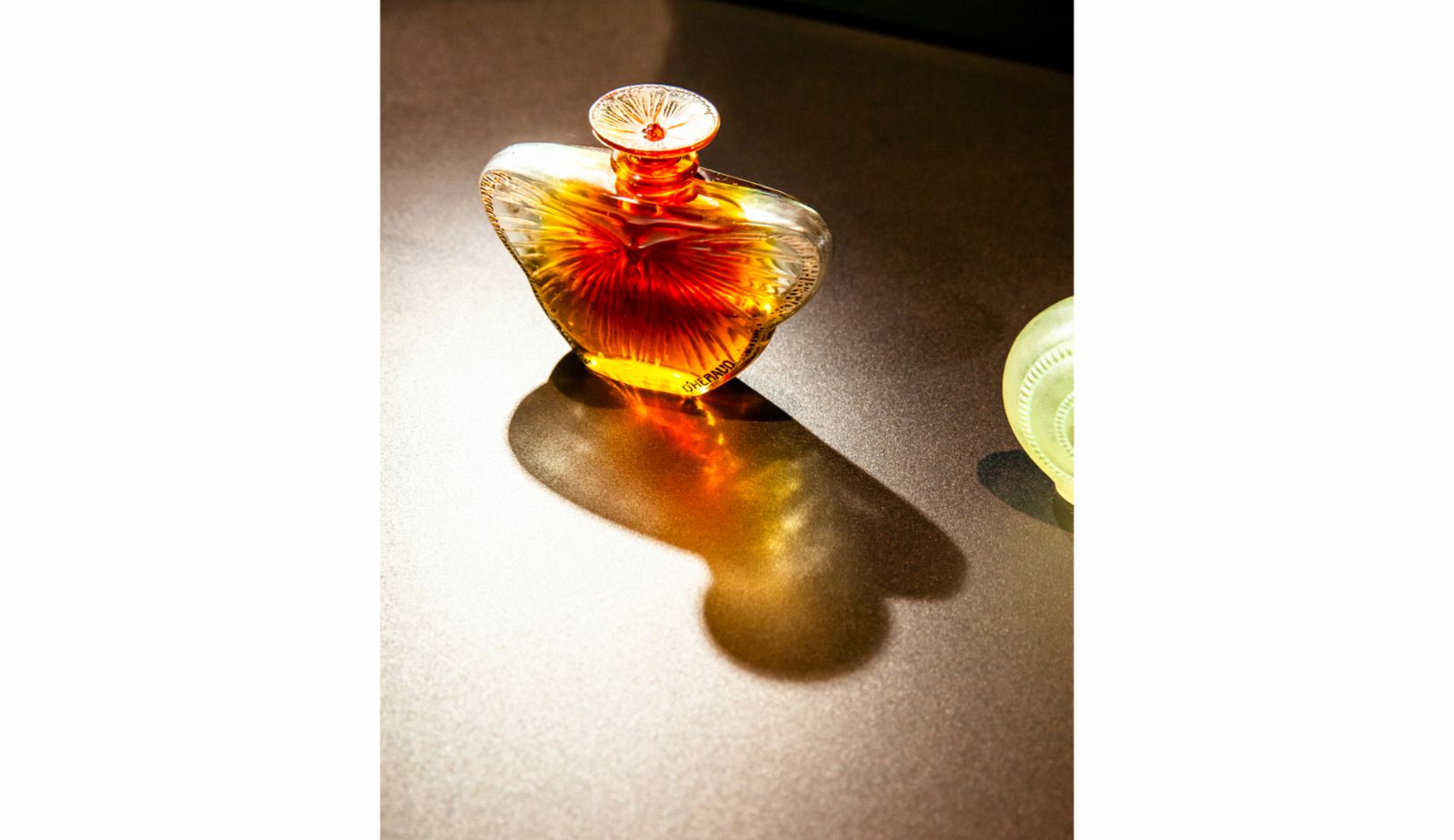

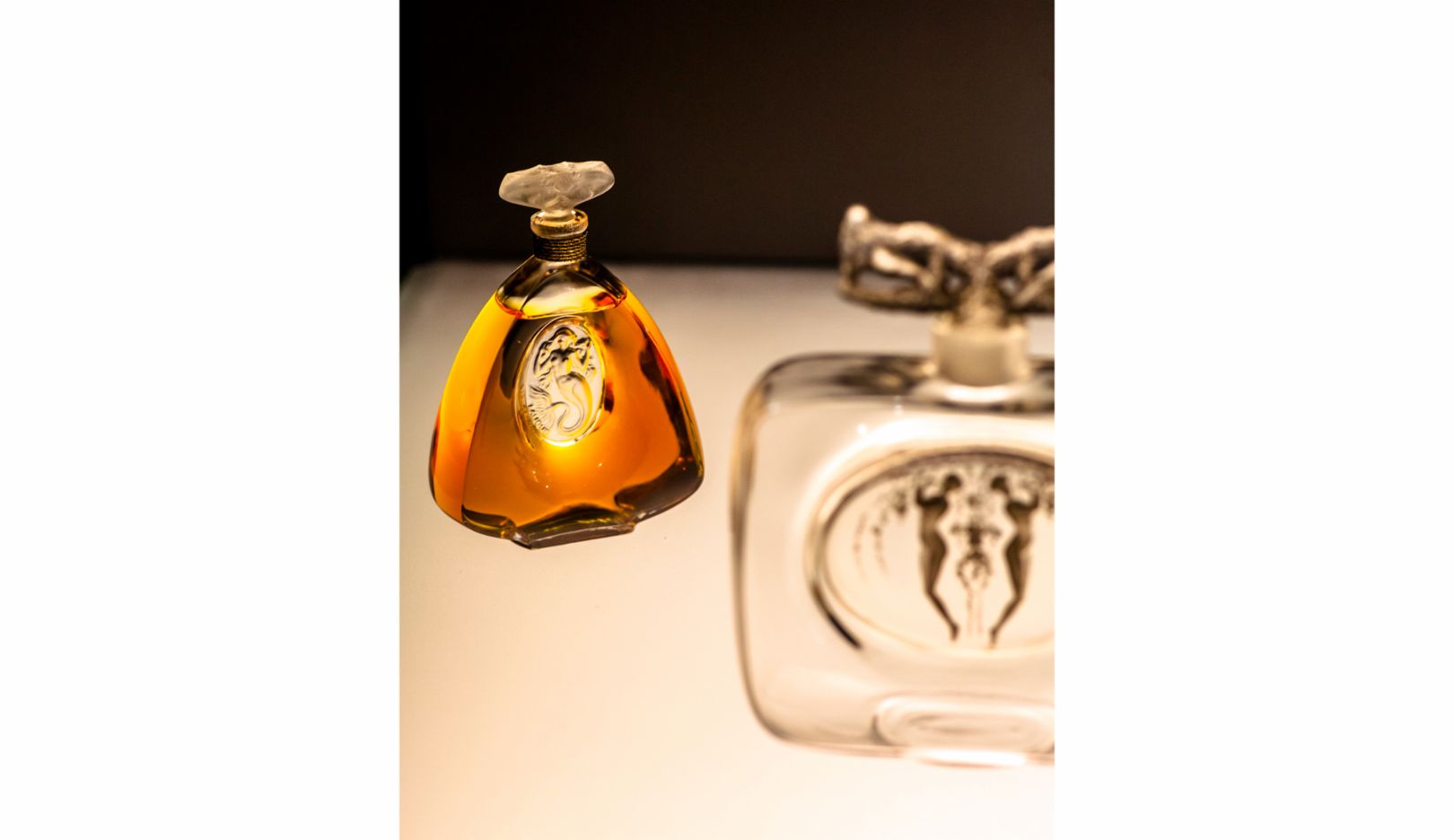

Intricate elegance:

The 7.3-centimeter-high “Fleurs parisiennes” bottle was created by René Lalique for Worth in Paris in 1929.One hundred years ago, René Lalique settled in Alsace with his glass art. Today, Silvio Denz preserves that heritage—through change.

This is what distinguishes the visionary: that he recognizes and uses opportunities; that he links things together that don’t seem to fit together at first glance. Silvio Denz was neither interested in whisky nor in crystalware. But his passion for perfume bottles opened up a new business segment for him. Denz comments, “Originally, I had no intention of taking over the crystal production of Lalique, and whisky was not on the agenda at all. But then my customer Macallan told me that the whisky stored in the old casks was dwindling and that he therefore wanted to keep the prices high. Good thing I owned the crystal production—we raised the value through the bottle. In 2003, we sold the first one for five thousand dollars.” Today, Lalique bottles whisky in crystal bottles, which have long been collectors’ items and can cost up to seventy thousand euros.

Money? Wealth? Denz demurs. He needs money to pay his staff. To develop the business further. In society, he says, they appraise you. “You’re on some richest people list, defined by material possessions.” No, money doesn’t make you happy. “You travel to the Maldives and decide to be happy. But then the food is bad and you get diarrhea. You can’t buy happiness; true happiness comes from within.”

Now that sounds almost Calvinistic. That Silvio Denz shuns public appearances and has avoided all manner of scandal also fits into the image of the disciplined businessman. But behind the image is a quiet eccentric. He has a pilot’s and diving license (the highest level), and he’s been driving a Porsche 911 Turbo S for twenty years—currently the fourth in a row, all in black. A Porsche Panamera awaits him in Bordeaux. He’s considering a Taycan as an additional sports car. Just as he appreciates the graceful delicacy of perfume bottles, he enjoys the sheer power of his Porsche.

“Opposites and balance are important. You can only appreciate your good fortune when you have a spot of bad luck as well.” His business acumen is balanced by his passions. Denz is passionate about architecture and art. He cooperates with Elton John, Damien Hirst, the light artist James Turrell; he’s worked with Zaha Hadid, Anish Kapoor, and many others. In his determined yet charming manner, he wins them all over. You take his word for it when he says, “Until I was twenty-four years old, I worked. For forty years, I’ve done what gives me pleasure.” For him, this includes a love of the French village of Wingen-sur-Moder, bucolic and rich in tradition. Far away from Paris and beyond Schwindratzheim.

Consumption data

Macan

Macan Turbo

-

20.7 – 18.4 kWh/100 km

-

0 g/km

-

A Class