Back to the Future

When Henk Spin purchased a 356 A Coupé as a restoration project, he had no idea that it was not a standard-issue vehicle, but rather a factory one-off full of special requests. Ten years later, the 1958 classic car had been restored to its former glory in the special color Porcelain White – with a whole host of extraordinary extras.

With the wind howling and the temperatures dropping, it’s not exactly a good day for a walk. The few who have ventured out into the dismal grey of the Dutch North Sea coast are rewarded with the sudden appearance of the Porsche 356 A Coupé in Porcelain White, its characteristic sound filling the air. The classic car heads down Korenmarkt in Hoorn, a small town north of Amsterdam, and comes to a stop at one of the many canals that rival even those in the famous capital city. No sooner has Henk Spin turned off the engine than passersby are pulling out their smartphones. A 356, especially one in this condition, is a rare sight here, too. But no one here realizes that this sports car, in particular, is not only extremely rare, but also one of a kind.

By the look on his face, the 65-year-old retired manager in the aviation industry loves nothing more than to take his classic car out of the garage for an unadulterated driving experience. After all, this 356 is a piece of history on wheels, a one-off full of special requests from a time when there was no official department for those at Porsche. And for Spin, the car represents one thing above all else: time well spent. Over a period of ten years, the Dutchman invested more than 3,000 hours in restoring the vehicle in his workshop, though that wasn’t initially the plan. “I bought the car because I was looking for a classic 356 from the 1950s as a restoration project,” says Henk Spin. “But when I started the work, I noticed a few things about the car were different than they were supposed to be.”

List of requests:

Whether toggle switch, Junghans clock, or telephone system – none of it was standard in the 356 in 1958.

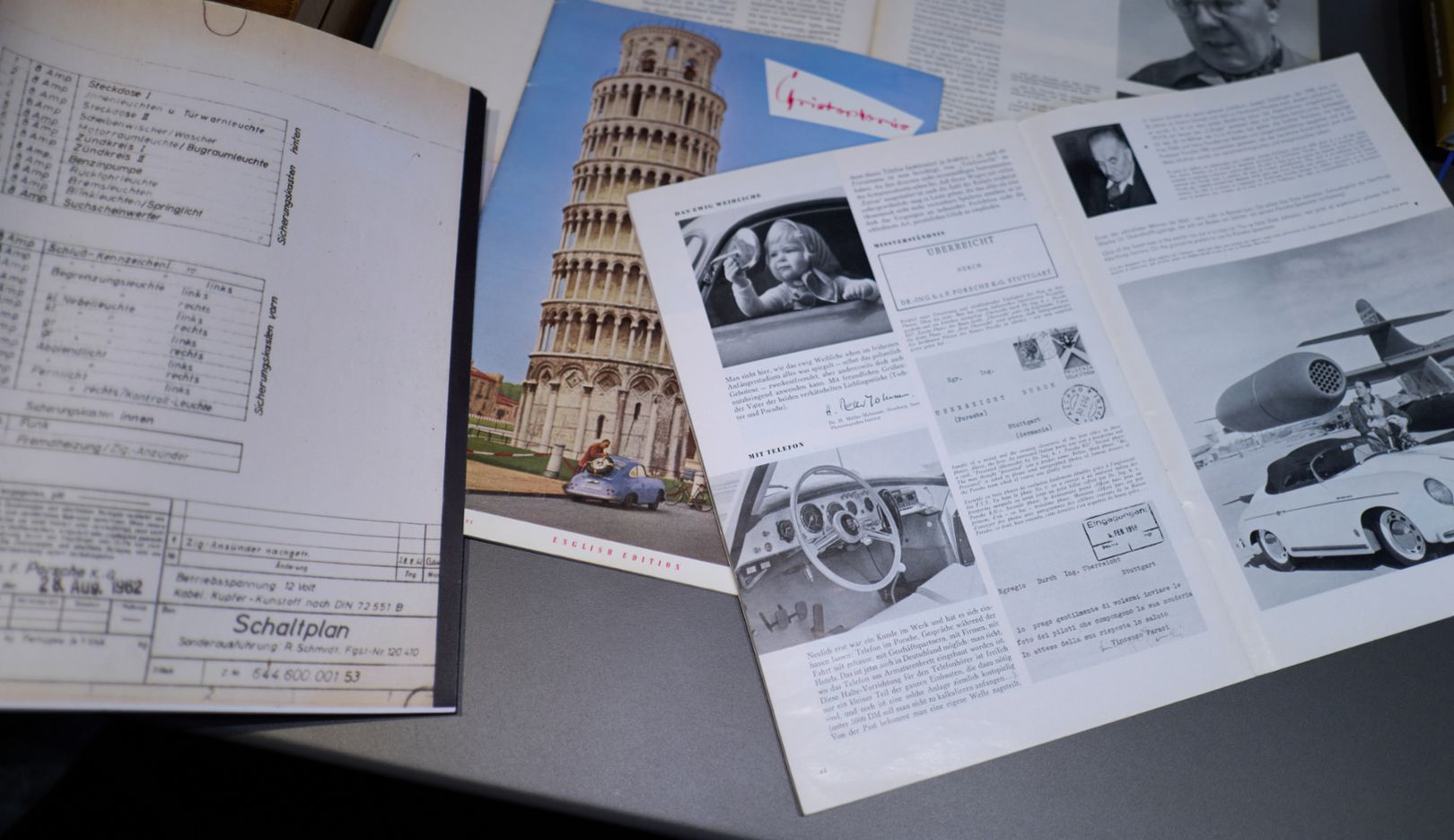

To figure out what was going on, Spin went to Stuttgart in 2008 to explore the Porsche company’s archive – and with the help of experts there, found an important clue. “On the original documents produced by Reutter, the vehicle body builder, there was something written in shorthand that no one could initially read.” Fortunately, Spin’s sister-in-law had studied stenography at school and was able to make out: “Reinhard Schmidt, Hannover.” The experts in Stuttgart promptly explained to Spin what that meant: this 356 is one of eight so-called Schmidt cars – all of them one-off vehicles – built by Porsche in the 1950s and 1960s on behalf of Reinhard Schmidt, with a list of special requests that defied all conventions. For Spin, the visit to the archive started an adventure that would fascinate him for years.

But who was Reinhard Schmidt? And why does the mere mention of his name in official vehicle documents spark such excitement? In the 1950s, Schmidt worked for the automotive supplier ATE. He also viewed himself as a test engineer and, more or less driven by personal interest, was active in testing vehicles, engine parts, and new designs, some of which were his own. Through his job at ATE, he cultivated good relationships with Volkswagen and Porsche and claimed to have more than 20 VW Beetles, eight Porsche models, and a variety of patents for the automotive industry. The eight Porsche vehicles were manufactured at the plant at his special request and were ahead of their time – sports cars with many highly unusual extras that had an almost fictional feel about them. Take, for instance, the 356 A Coupé that Henk Spin is now driving along the dike toward the garage.

Restorer and collector:

Henk Spin in his office, with a nearly complete Christophorus collection on the shelves.“Porsche introduced a lot of what we see in this car in series production years later.”

Henk Spin

According to official documents, the car with chassis number 102324 was delivered to Reinhard Schmidt as a plant sale on February 1, 1958. Just as it was back then, the 75 PS engine from the 356 1600 Super is installed at the rear, delivering a top speed of 170 kmh. Later that same year, an article appeared in issue 32 of Christophorus that focused on one of the many extras: “A customer was recently at the plant and had something truly extraordinary installed in the Porsche: a telephone for conversations with home and business partners during the drive (...).” While this is now possible in Germany, it goes on to say, you shouldn’t expect to pay anything less than 5,000 deutsche mark. “The post office assigns you your very own wave, as this telephone works without a wire. Yes, even a private person is authorized to have their own ‘telephone wave.’ You can tell by looking at the many different nonstandard instruments on the dashboard that this car is fitted with a whole lot of extras (...).” As amusing as this text now sounds nearly 70 years later, it still reveals something astonishing: Schmidt was willing to pay nearly half of the cost of the new car for the telephone system alone. And that’s just the highest of a great many individual costs on his list of special requests.

Dream vehicle:

Door panels in Acella Red, seats in white napa leather, carpets in mottled beige – Reinhard Schmidt came up with all that on his own. Nearly 50 years later, Henk Spin began restoring everything to its former glory.Henk Spin parks the 356 in his workshop at the edge of town. A 2018 Macan and a 2006 Cayman S – both white – are parked in front of the door. The next restoration project, a 911 T (original 911 built in 1972), is awaiting its turn on the lifting platform next to the 356. There’s also a 911 Carrera S Cabriolet (991) parked at his home. With his tools painted in classic Porsche Red and framed photographs of his rally competitions hung on the wall, his pure passion is also impossible to miss in the workshop. Upstairs on the second floor, there’s a wall full of historical racing posters, and another dedicated to around a hundred signed autograph cards of race car drivers. Porsche is everywhere you look. Even Richard von Frankenberg, the former race car driver and Editor in Chief of Christophorus, is immortalized here. The office features two shelves full of books about cars, other Porsche memorabilia, and an almost complete Christophorus collection, with just three issues missing. But with the main character waiting downstairs, there’s no time to take it all in.

“When the car that I had bought from a restorer in the US state of Arizona was unloaded at my doorstep, it looked worse than I had feared,” explains Spin. “I had to repair most of the body. And I had to rely on the help of experts for just about every other component.” Chassis, engine, electronics, seat upholstery – Spin had to track down a specialist for every part of the job. Much of it, including a new nose, came from Porsche Classic. “I had to learn to be patient. It took nearly four years to get all the parts of the body together. Then I began putting the puzzle pieces together.” And gradually the 356 began to take shape and resemble its original form, just as it was described in the certificate of delivery issued by Stuttgarter Karosseriewerk Reutter & Co. to Porsche in January 1958: painted in the special color Porcelain White; door panels, dashboard, and backrest in imitation leather, antique grain, Acella Red; seats in white napa leather; window trim painted red; buttons in light beige; carpet in mottled beige; turn signal switch and steering wheel in beige, and specially designed electric systems and antennas. Production at Reutter took around five weeks longer than it does for a series production car.

But the Schmidt car is an extraordinary puzzle, which is why Spin had to not only collect classic car parts, but also do some detective work. He points to two binders jam-packed with historical photos, articles, emails with archive employees, and copies of original documents. “With the help of experts and all the documents, I was able to get closer and closer to the Schmidt car’s original form over the years,” says Spin. All the nonstandard extras and instruments can now be seen again in all their glory. In addition to the special colors Porcelain White and Acella Red, the most eye-catching features are the Lorenz telephone system with its 50-centimeter antenna, the Blaupunkt Köln No. S 914.551 car radio, and a replica of the original red license plate, which identifies the car as a test vehicle. “It takes patience to track down exactly the right telephone or radio,” says Spin. “After all, they were produced nearly 70 years ago.”

As you wish:

Additional round instruments, toolbox below the front passenger’s seat, and engine bay lighting.

But Reinhard Schmidt’s special requests didn’t end there. Additional extras onboard included the engine bay and trunk lighting; a hazard light activated with a toggle switch to the left of the speedometer; a speedometer from the 356 Carrera; a tachometer from the 356 1600 Super; to the left of that, a Junghans clock that was also installed in the 356 A 1600 GS Carrera GT rally car; a toolbox below the fold-up front passenger seat; exclusively toggle switches; a portable rally light; a turn signal switch to the right of the steering wheel; speakers in the door panels; reverse lights; and an electric pump for the windshield wiper fluid instead of the typical foot pedal. “Versuchswagen 145” (Test Car 145) also appears on yellow plates at the front and rear. Everything is now like it was nearly 70 years ago, all of it restored by Henk Spin.

“Porsche introduced a lot of what we see in this car in series production years later. In some ways, all of the Schmidt cars were vehicles from the future,” he says, a smile flashing across his face. Knowing that there’s no other car like this anywhere in the world is, without a doubt, something truly special. Especially when you’ve invested ten years in restoration and, with the necessary skills, a whole lot of passion, and a bit of luck, breathed new life into a piece of history. “While there may be some who view all of that as an economically unjustifiable indulgence, the enjoyment of technical perfection isn’t the worst way to experience personal happiness,” says the Christophorus article from 1958 in closing.