Into the Past: Lviv Grand Prix

Porsche Central and Eastern Europe – History repeating: Taking the Porsche Macan S on a forgotten racetrack in Ukraine’s cultural capital to remember a great time in motorsport—and the beginning of Ferdinand Porsche’s passion for racing.

Today we’re in the center of Lviv driving the Porsche Macan S around the most Eastern European Grand Prix route, a track renowned for its incredibly difficult turns and challenges that have remained unchanged in 90 years.

Currently the cultural capital of Ukraine, Lviv is a city with a unique history. In the twentieth century it was a part of five different countries. Its walls have seen not only sieges and cannon fire, but also battles of the greatest racing drivers on earth: Rudolf Caracciola and Hans Stuck, Pierre Veyron and Ernst Burggaller. The Lviv Grand Prix, held between 1930 and 1933, is one of the least known races in the interwar history of motorsport. It is worth noting that the cars designed by Ferdinand Porsche or under his leadership—Austro-Daimler ADM 6 Sport and ADR 12/100, Mercedes SSK and SSKL—have won here more often than other great competitors such as Alfa Romeo, Bugatti and Maserati. It is also significant that Stuck and Burggaller would later become Porsche’s associates in his own business. After two decades in senior positions at Austro-Daimler and Mercedes-Benz, Ferdinand Porsche opened his own design studio developing both civilian and race cars. And both racers were fully involved in this process—not only testing cars and piloting them, but also procuring orders and funding.

Lviv highway is a genuine street circuit. There is simply no other street track like it in the world that remains in its original form. In Monte Carlo, Pau, Brno, Geneva and Barcelona, curves were smoothed, roads widened, bumps cut off, and asphalt replaced paving stones. In Lviv, everything is the same as it was in the 1930s: neither the configuration nor the surfacing have changed one bit. What racing fanatic could resist the temptation of driving on a 90-year-old track? Thanks to old photographs the exact point of the start-finish line is known down to a couple of centimeters as well as the trajectory of the bends. So let’s go! But first, don’t be fooled by the choice of the Macan S for this race: smooth, fast driving over uneven road surfaces is simply impossible without energy-intensive air suspension.

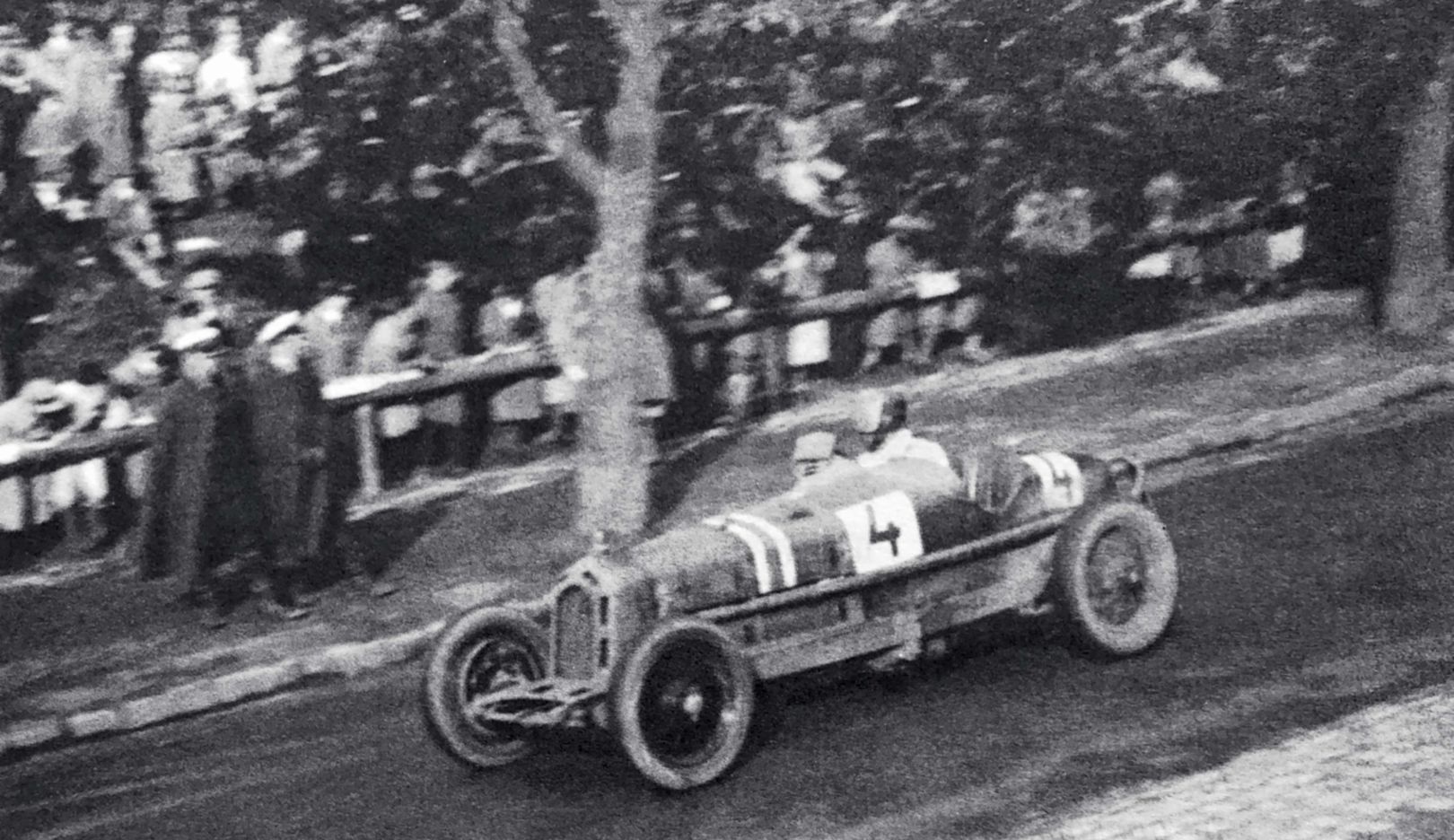

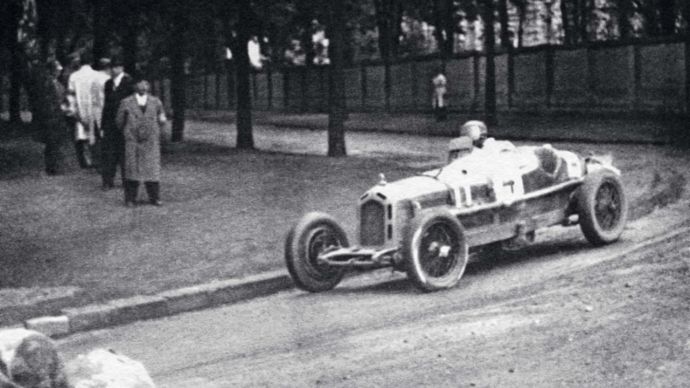

Spot the difference:

Times may have changed, the spirit and fascination remain the same. With the Porsche Macan S, the streets of Lviv are still fun, despite the speed limit.

Now, it’s hard to imagine that Lviv residents were among the first to see the advantages of this racing format, but the fact remains that the plans and documentation for the street circuit were already complete back in 1928, a year earlier than the Monte Carlo circuit. The chosen streets were Pelchynska, Stryiska and Hvardiiska, connected in a 3,041-meter “Lviv triangle”.

A variety of elements including narrow streets, 55-meter height differences and unique surfaces compensate for long, straight sections that make up 59 percent of the circuit with relatively few turns (eleven right and eight left). The start is at the entrance to Stryiskyi Park, followed by a double right turn, which leads to a long rise. Not only does the road go up, it twists like a snake changing its old skin. Several turns later and the “triangle” falls down even more rapidly, like an attacking eagle.

“I am delighted with the track. I could not have imagined that I would find anything like it here. It is first class and in no way inferior to the Monte Carlo racetrack.” Hans Stuck

With a pavement lined with basalt masonry, only tram tracks can compete in rainy, slippery conditions. And it was raining cats and dogs in the capital of Galicia, only one of the four street races that took place in dry weather. Tram lines were also present on other routes like Grenoble and Porto, where drivers could cross them, but in Lviv they had to drive almost a third of the distance along the rails. As a result, after the very first race the track was classified as one of the most difficult and dangerous. Many teams simply did not dare to compete in Lviv, but Mercedes was not among them. Ferdinand Porsche designed the greatest sports car of the 1930s, the Mercedes SSKL, which was equally at home in a rally, on a circuit, or on mountain roads. A racer himself, Porsche loved to solve these multi-dimensional problems. Having barely built his first car, the 25-year-old engineer won his debut race at Semmering in 1900. Porsche’s subsequent creations achieved the same feat. Even today, each new model is a strikingly impressive fusion of power and sporty character. The Macan S is a Cayman in a crossover format: as agile as a salamander and as quick as a mamba, from a standing start it can overtake a jet plane.

Visiting “the George”

In a nod to tradition we stay at the George Hotel, where other racers were accommodated by invitation only. Despite its location in the very heart of the city the hotel offered the drivers a good night’s sleep because it occupied almost an entire block and had its own “subdued acoustics” due to the inner courtyard. It was extremely important to get enough sleep as the training races took place between 4 am and 6 am. “The George” became a kind of racing hub—flyers were posted and releases were announced at the entrance and in the foyer. And the restaurant was used as a trophy room where prize cups were displayed, together with the “Grand Prix” in the center.

Tough times:

Motor racing in the 1930s was an adventure with an uncertain outcome. In 1932, only two cars crossed the finish line.We rise in the middle of night so that by 4 am we are at the entrance to the park. Here we find the starting grid, together with depots, a judge’s bridge and two of the five stands. In total the stands held 3,900 spectators, and despite the extremely expensive tickets and rampant inflation of the early 1930s, the seats were always occupied. Even when it rained the race would attract 50 to 60,000 spectators—a solid figure for a city of 295,000 inhabitants—and up to 5,000 spectators were up early enough to watch the training at dawn. But today, our unwitting timekeeper is a lonely janitor sweeping leaves at the Citadel.

Even when it’s dry, the paving stones are as slippery as soap and much more uneven than it seemed during yesterday’s inspection drive. How Caracciola “Carach” was able to accelerate to 200 kmh on these bumps is beyond me. They say he was the only driver who could flatten the trajectory as much as possible, slipping into the smooth tram rails. “On Pelchinska Street the rails were filled in during the races with a plaster mix”, as science fiction writer Stanislav Lem recalls from his childhood in Lviv. Caracciola clearly earned his title of the Rain Master for his faultless driving in wet conditions.

00:00

A straight 900-meter pit stop section merges into a double right turn which then leads the cars on to a long ascent. Leaving the rails, the Macan exhales with relief, the stabilization system calms and the PDK continues to change gears at the speed of a revolver. “During the lap, I made 29 to 36 switches,” recalled Ian Ripper, one of the most productive drivers of the “triangle”. “The whole race was physically and mentally exhausting.” You can imagine how the less experienced drivers would have managed—sometimes they were literally lifted out of their cockpits. It was here at Lviv that three great names in racing started the Grand Prix: the Polish racer Maria Kozmiyanova, the French racer Anne Rose-Itier and the Italian Countess Vittoria Orsini.

I must contain my excitement! Like a mantra I repeat: “This is not asphalt!” I sing an ode to the Stuttgart engineers because every year they blur the line between the sports car and the crossover essence of the Macan even further. The thrust vector control system is particularly impressive. With additional rotation impulse around the vertical axis, it literally pushes the crossover into the steep turns, but at the same time the electronics do their work with impressive tolerance—my ambition as a driver has not dwindled in the slightest.

01:15

Here on the long ascent beside the old cemetery was the only place on the track where drivers could catch their breath. But even here accidents have happened. At a training session in 1932, Alfred Broucek took out a lamppost with great accuracy. The Macan, on the other hand, takes this series of turns, which are not as simple as they might appear at first glance, quite smoothly. It sticks to the road like a tram on rails.

In 1933 the Grand Prix lasted three hours and towards the finish line there was almost no need for drum brakes. The “hairpin” that took the riders over the finish line sometimes may as well have turned into a salvage yard. It was forbidden to stop in that turn, so the seats on the balconies of that intersection were sometimes more expensive than in the central stands. “People were sitting everywhere—even on the rooftops and a few of the bravest climbed up the high brick chimneystacks,” the Warsaw Sports Review reported. Somewhere along the line Porsche introduced the axiomatic idea that “the brakes must be ‘more powerful’ than the motor so a driver could correct the situation if he or she made a mistake.”

Green machine:

Driving the Macan S around the curves of the former racetrack is fun. And it’s much more comfy than it was back then.

01:51

The only chance of survival for those who made mistakes and flew into the sandbags was to hobble the hundred or so meters to the pits. Sometimes the tragedies that unfolded there were as dramatic as those that took place on the track. Hot headed drivers would often collide as they entered the depot, just like at Le Mans in 1955. “Engines off” was a strict requirement in the pit stop, but given the hellish fuel compositions of the time the vehicles were often extremely difficult to restart. And so a four-minute hitch caused by a malfunctioning ignition system cost the almost victorious Wiedengren the final victory in the 1933 Grand Prix. He was outstripped by Eugen Björnstad who simply hadn’t stopped to refuel. But many years later in 1985 the Norwegian admitted he had secretly installed two extra tanks in his Alpha. One of these tanks was installed behind the dashboard and had ruptured in the middle of the race, causing methanol-based fuel to splash into his face. This forced him to stop right in the square where he could secretly wipe his eyes while feigning a broken steering wheel.

02:00

Alas, that Grand Prix was to be the last. Amid the dire economic crises of the time the 1934 race was cancelled. The organizing committee transferred the profits from the 1932 and 1933 races into a fund to fight unemployment, but it was itself dependent on the city’s treasury.

It wasn’t until 2000 that the street race resumed, but this time in the Leopolis Grand Prix retro rally format. Participants came from literally all over Europe, driving an impressive range of sports models including the Porsche 356, 924, 928 and 911. After all, if you own a classic Porsche sports car, how could you resist the enormous pleasure of driving on a Grand Prix track that has remained unchanged over an incredible stretch of 90 years?