The Mind Is Free

Although the Iron Curtain divided Germany, Porsche fans in the Communist part of the country still realized their dream of a sports car—and with the active assistance of Ferry Porsche. Remarkable tales to mark the thirtieth anniversary of the reunification of East and West.

Courage and a Dream

It was June 17, 1953, just eight years after the end of the Second World War, and Soviet soldiers were on the march in Dresden again. Shots rang out in the streets. Like in Dresden, citizens all around East Germany were rising up against the Communist regime installed by the Soviets. For a brief moment it seemed as if the people just might succeed in winning their freedom, but then the Volkspolizei (East German People’s Police) and the Red Army crushed the nationwide uprising. Dresden was still marked by the devastating bombing it had suffered in the war. Large parts of the city still resembled a stone desert. World-famous buildings such as the Frauenkirche (Church of Our Lady) and the Zwinger, a once magnificent palatial complex, lay in ruins.

Hans Miersch had been through a lot in his thirty-two years. Ten years earlier, the native of Saxony had been seriously injured in the war. His right lower leg had been amputated.

Just under forty kilometers away from Dresden, in the small town of Nossen, Miersch set up a women’s shoemaking workshop. A bold undertaking in the Communist part of Germany. Private property was frowned upon; large companies were nationalized—as the property of the people. The planned economy was the law, and private initiative represented an undesirable element.

Yet Hans Miersch had no intention of being deprived of his dreams, either in professional life or his private affairs. In the early fifties, he discovered the new Porsche 356 in a West German car magazine. As he recalled decades later, “From the moment I saw the first models, I knew: This is my dream.”

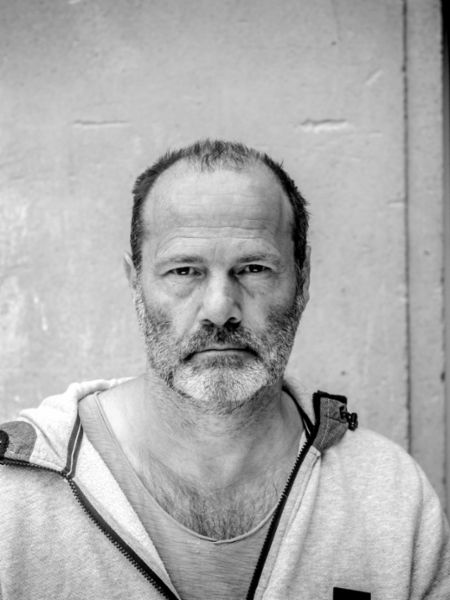

Undying love:

Even after the fall of the GDR, Hans Miersch (here circa 1993) retained his old license plate number out of a traditional attachment to his automotive life companion. Both—the car as well as its promoter and owner—survived socialism at an advanced age.The shoe manufacturer shared his dream with many a car fan in East and West, but just as for most of the others, it seemed unattainable for Hans Miersch. The two German states were worlds apart. Although travel between East and West was still possible—the wall was not built until 1961—the German Democratic Republic imposed strict restrictions on trade with the capitalist Federal Republic of Germany. Even an entrepreneur like Miersch was not allowed to import a luxury car from there. His company car was a self-built creation with a Hanomag body and the chassis of a former Jeep-style Kübelwagen. Back in the day, the rear-wheel-drive, open-top four-seater had been designed by Ferdinand Porsche as the Type 82. “The car ran wonderfully,” said Miersch of his unusual vehicle. Equipped with a trailer—also self-built—he traveled the “sister countries” of Hungary and Poland, delivering his ladies’ shoes. His connections reached as far as Czechoslovakia, which would later prove fortuitous.

Finding a scrapped Type 82 was not particularly difficult in the GDR. Amid their helter-skelter retreat in 1945, German soldiers had to leave them behind on the eastern bank of the Elbe in order to save themselves by swimming westwards. More than a few farmers in the Dresden area therefore still had a Kübelwagen in the barn.

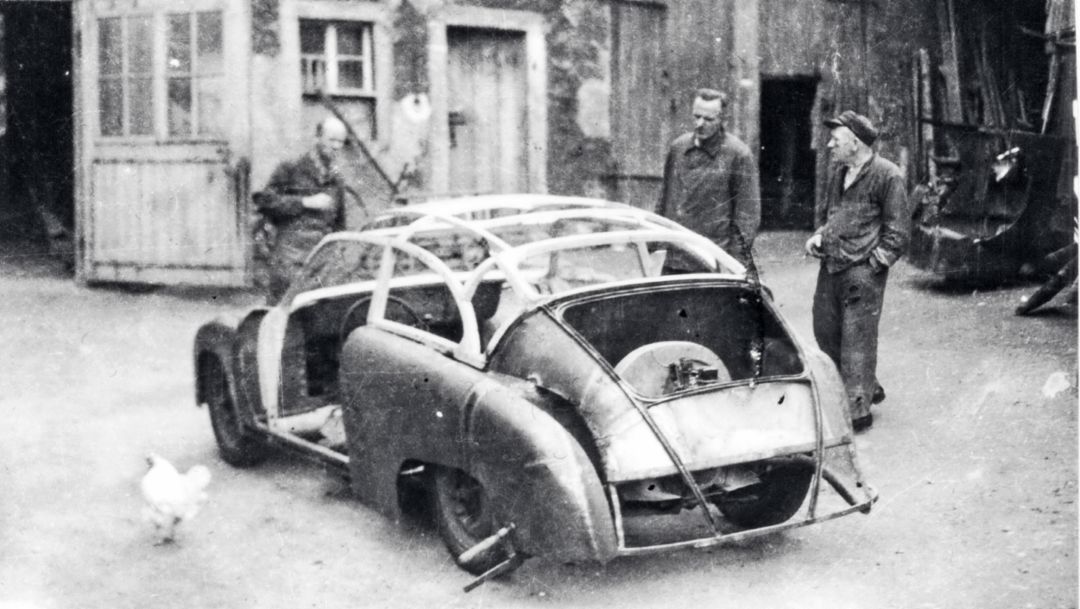

And just such a Kübelwagen also marks the beginning of this magical story. The twin brothers Falk and Knut Reimann, twenty-one-year-old students at the Technical University of Dresden, designed a coupe on the drawing board that looked strikingly similar to the Porsche 356. Miersch caught wind of it. The budding engineers Reimann found another ally in coachbuilder Arno Lindner of Mohorn near Dresden, who put their designs into practice. He constructed a skeleton of ash wood over which the body could be pulled and then bolted or welded to a chassis. Lindner's family business had a wealth of experience with constructions of this sort: indeed, his grandfather had built horse-drawn carriages according to this principle.

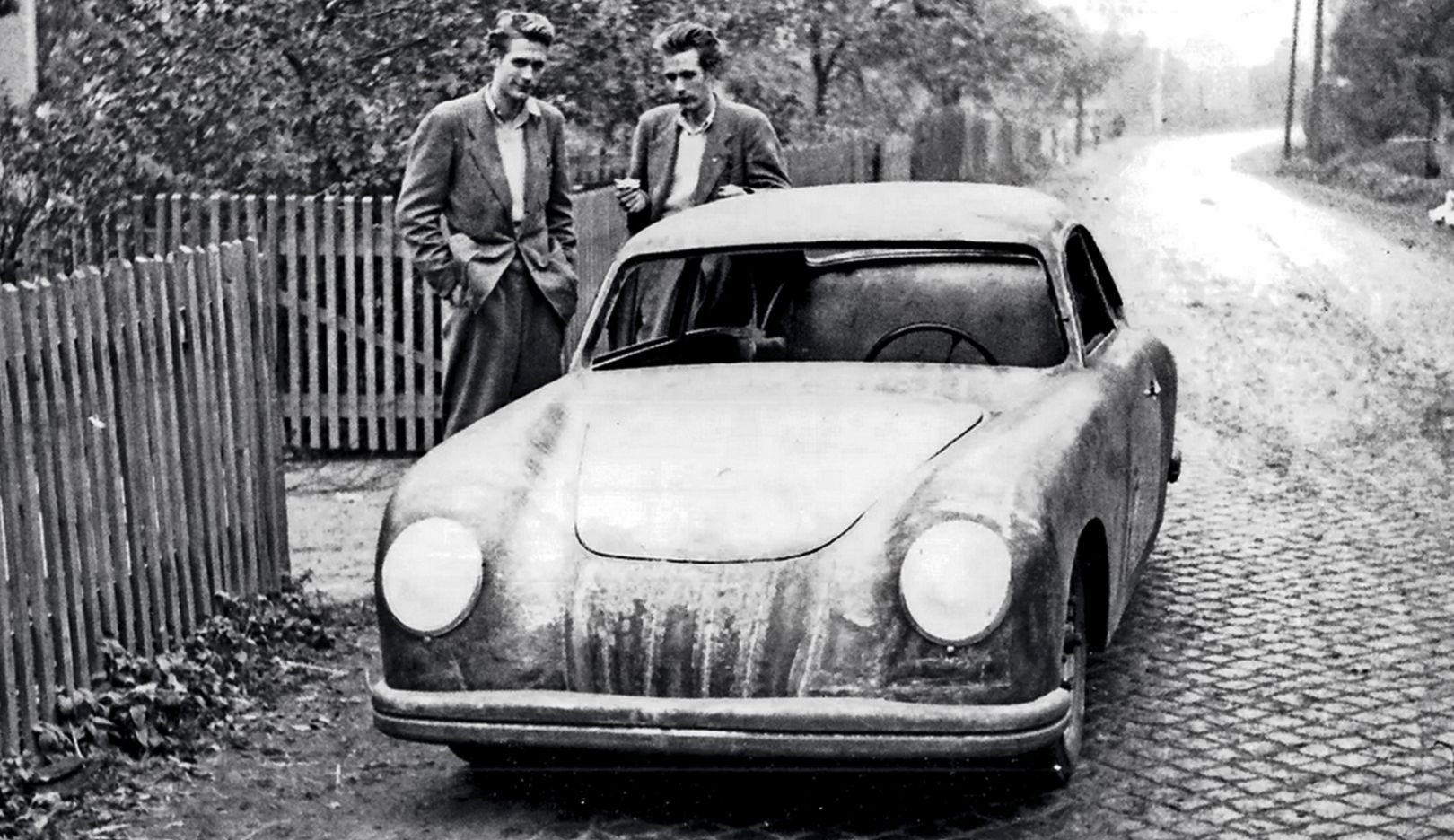

Gifted dreamers:

Prospective engineers Falk and Knut Reimann came up with the design for the GDR Porsche. Like Miersch, they were also actively supported by company boss Ferry Porsche. In their own model, the inseparable twins embarked on many adventures. They drove as far afield as France and the Alps.He secretly smuggled the Porsche parts across the East German border in a briefcase.

Miersch procured a Kübelwagen chassis as the basis for his dream of an eastern Porsche. At this point, however, a serious problem emerged that called into question the entire operation: no sheet metal of suitable quality could be found in East Germany. Miersch ultimately tapped his relationships in Czechoslovakia to obtain around thirty square meters of sheet metal. “It was almost worth more than gold.” With a wall thickness of one millimeter, it was quite heavy; the hood alone weighed almost twenty kilograms. And since the chassis of the Kübelwagen was around thirty centimeters longer and considerably wider than the body of the Porsche 356, the Miersch 356 became a spacious four-seater—which in turn meant further additional weight.

The hunt for parts for the chassis and drivetrain turned into a real adventure. A brake system for the Porsche 356 A was procured from the West Berlin dealer Eduard Winter through the personal mediation of company founder Ferry Porsche. Miersch smuggled the precious goods from West to East “in a very large briefcase,” sweating bullets all the way—smuggling, after all, was punishable by long prison sentences in the GDR. “Several times a day” he had to cross the border under the scrutinizing gaze of East German soldiers; “the brake drums in particular were incredibly heavy.”

Little by little, the car began to take shape. After seven months, in November 1954, the self-made vehicle was ready for the road. Lindner charged 3,150 West German marks for the production of the body.

Home:

The Miersch has been at home in Würzburg for the last twenty-five years. It has grown ever more beautiful with age.Initially, the Miersch was powered by a weak 30-hp boxer engine, which struggled with the 1,600-kilogram vehicle. The original 356 prototype weighed only about half as much, and had twice as much engine power to boot. It was not until 1968 that Miersch was able to install an engine of suitable stature: a 75-hp, 1.6-liter Porsche engine. He was allowed to import the dismantled engine—ostensibly a gift from a West German relative—as automotive spare parts.

In a letter, Ferry Porsche wished the young men pleasant driving with their self-built Porsche.

Lindner produced roughly a dozen other coupes based on the same prototype in the mid-1950s; the exact number is not known for certain. What is certain, however, is that the two designers, the Reimann brothers, had one built for themselves as well. They, too, hoped for help from Zuffenhausen—and they, too, received it. In a reply to the “Messrs. Reimann” dated July 26, 1956, Ferry Porsche wrote: “To help you out of your predicament, we will be sending you a set of used pistons and cylinders as per your request in the coming days by way of the Eduard Winter company in Berlin.” He went on to wish the two gents “good luck in taking receipt of the parts and pleasant driving with your self-built Porsche.” The letter was signed by Ferry Porsche’s secretary. The head of the company himself was, as he said, “currently at the race at Le Mans.”

For as long as they could, the Reimanns undertook extensive tours through Europe in their self-built car. To save money for the travel fund, the twins shared one driver's license between them for years. The ruse was never uncovered. Snapshots of the two over the years show them with different girlfriends at the Großglockner, at Lake Geneva, in Paris or Rome. At the center was always their greatest love, the Porscheli, as they called it. The western-oriented lifestyle of the two sports-car replicators was not lost on the ubiquitous spies of East Germany’s secret service. Shortly after the wall was built in 1961, both were arrested for allegedly abetting escape attempts. Nearly a year and a half went by before the two were released from prison.

And with that, all traces of Porscheli would be lost for decades. It was not until 2011 that Austrian collector Alexander Diego Fritz discovered the car and saved it from ruin. As far as anyone knows, only two of those GDR Porsches have been completely preserved: the fully restored car owned by Fritz, and the largely still original car built by Hans Miersch. It had remained continuously in the hands of its first owner, including the original RJ 37-60 registration number. When Miersch’s shoemaking operation was converted into a state-owned business in the early 1970s—in other words, expropriated—he managed to protect the car from state intervention. Miersch cunningly used his war wound as a rationale for keeping it: “It is a personalized, self-built vehicle designed specifically for me as a disabled person.” He said it was worth 1,800 East German marks. From now on, the former factory owner had to earn his living as a worker in a roofing paper factory.

Between worlds:

The silhouette looks familiar, though the proportions are somewhat eccentric.By the time the history of the GDR came to an end thirty years ago, Miersch had reached retirement age. He remained faithful to his beloved car even in a united Germany, painstakingly beautifying it and improving it all along. At long last, a 90-hp engine from a Porsche 356 enabled the heavyweight champ to achieve reasonable driving performance.

It was not until 1994, at age seventy-three, that Miersch decided to part with his life companion, now painted white. He found a worthy successor in the Würzburg Porsche enthusiast Michael Dünninger. Wherever Dünninger shows up with the car, he causes a bit of a stir. “Many recognize the similarity to the 356, but are still perplexed by it,” says Dünninger with a laugh. And over time, he too has made some improvements. He had the seats reupholstered with a cognac-colored leather, for example, and swapped the pre-war speedometer from Horch for an original Porsche part. All adaptations aside, the Miersch remains a compelling piece of contemporary history. Developed in an epoch in which the world was divided into east and west. And in a time when people could still build their automotive dreams themselves.

German-German cultural heritage:

Owner Michael Dünninger only drives his Miersch on special occasions nowadays.

The dignity of age:

Sixty-five years of history reside within the Miersch. A product of a strong will.

SideKICK

9:11 Magazine: The self-built car in film

A series of moving pictures at 911-magazine.porsche.com tell the moving tale of how Falk and Knut Reimann constructed their Porsche replica. And the model in which the twins went on their European tour still exists today. Or rather: again.

Unlike the lovingly maintained car of Hans Miersch, it had moldered for decades in undeserved oblivion. Austrian Alexander Diego Fritz restored the car and wrote a book about it in 2016: Lindner Coupé: DDR Porsche aus Dresden (Lindner Coupé: a GDR Porsche from Dresden, not yet available in English).