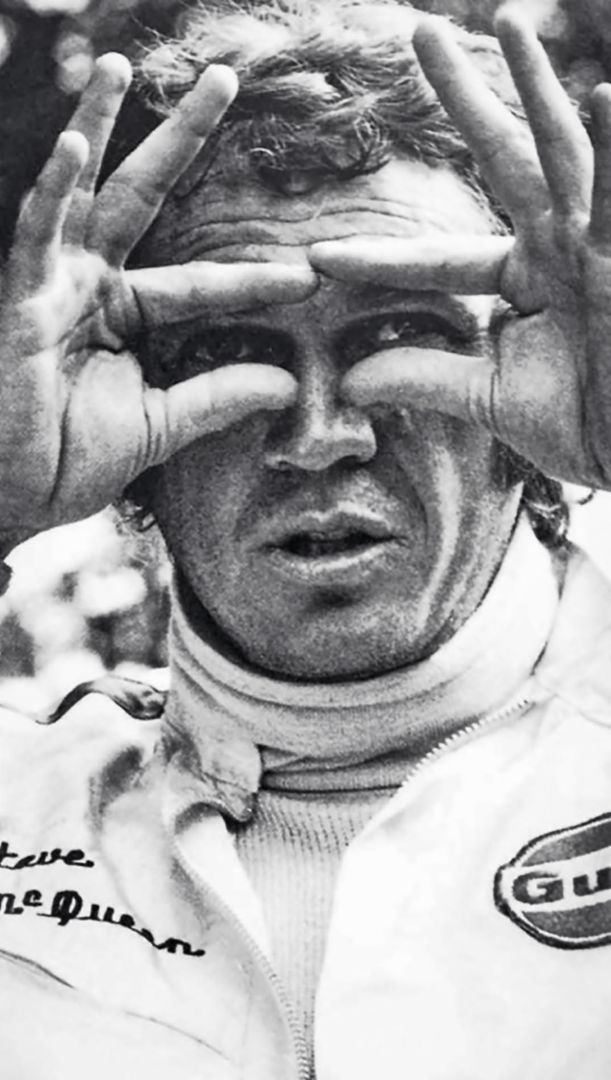

McQ: The Man Who Called Himself Harvey Mushman

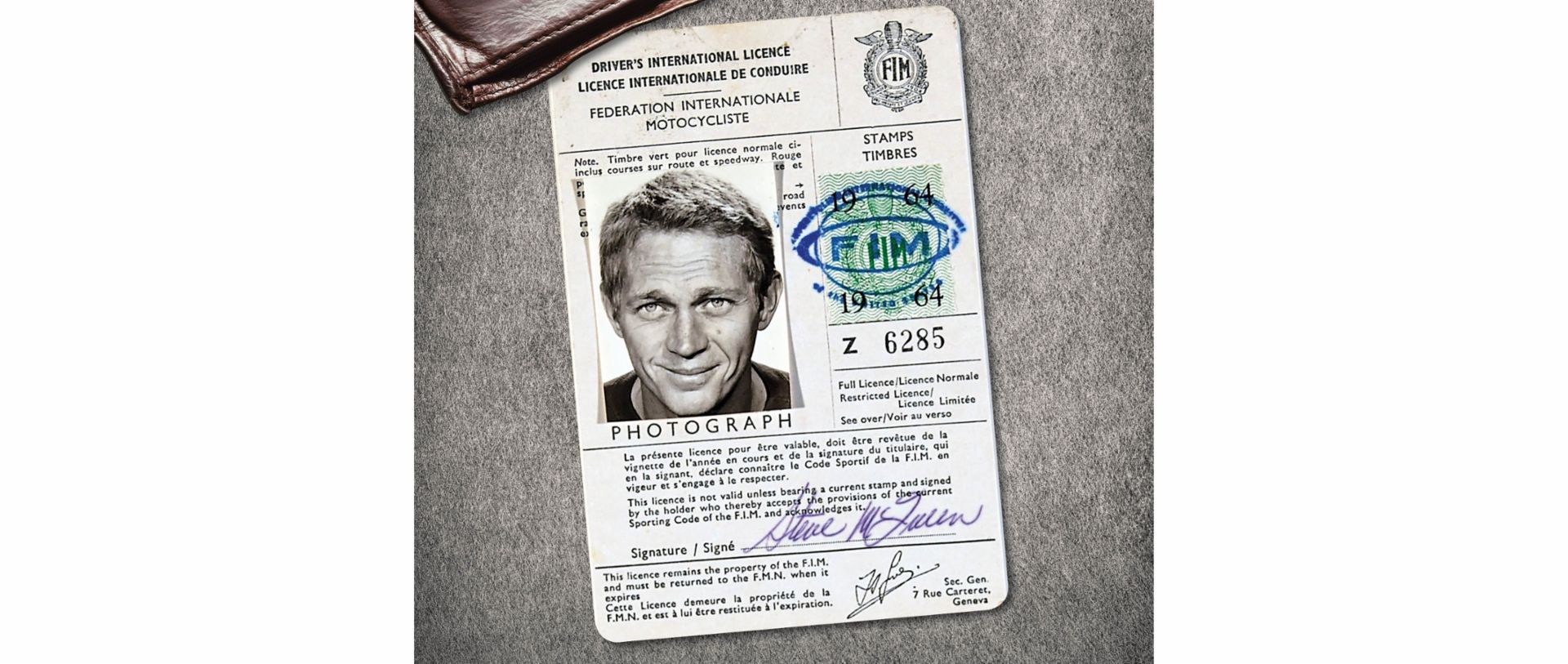

Addicted to motorsports: Hollywood star Steve McQueen, who would have turned ninety this year, pursued his passion as a private racer in uncompromising fashion.

“I’m not sure whether I’m an actor who races or a racer who acts.” Steve McQueen

The congratulations from Zuffenhausen arrived by airmail: “Dear Mr. McQueen,” the letter dated March 1970 began. “It is a great pleasure to extend my warm congratulations to you on your outstanding performance at the 12 Hours of Sebring.” Ferry Porsche wrote that he had “followed the race from home with rapt attention.” Forty years old at the time, McQueen was not only one of the most successful Hollywood stars of the day, but also an avid race-car driver: “You can imagine how delighted I was that you posted such a brilliant result in a car of our brand,” concluded Ferry Porsche.

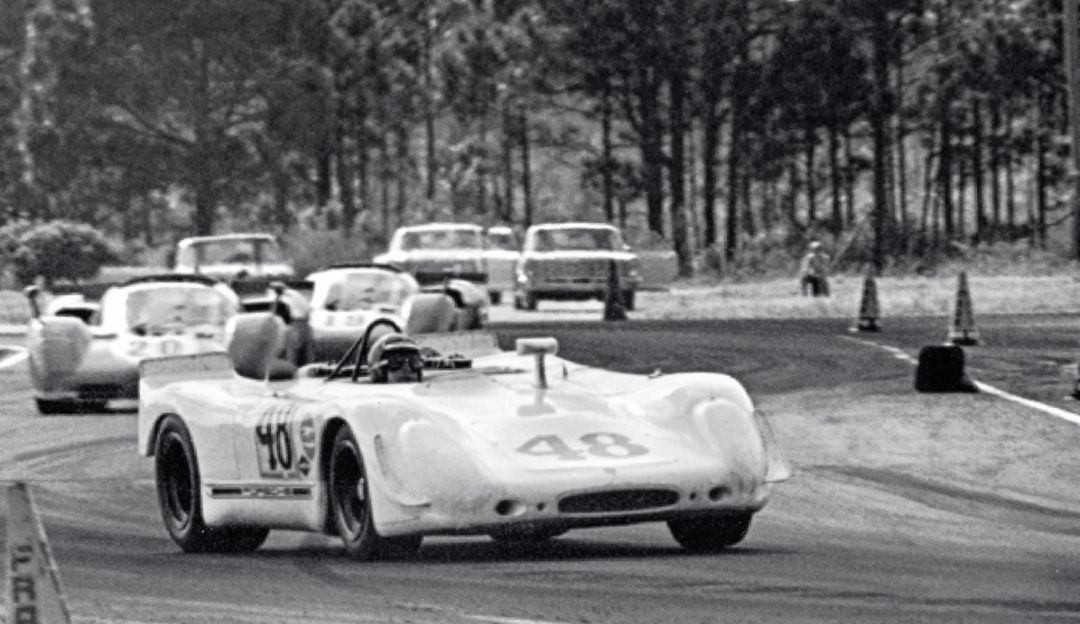

1970 Sebring

Twelve-hour race: Steve McQueen celebrates one of the highlights of his racing career—his second-place finish in a Porsche 908/02 Spyder KH (short tail) during the Manufacturers’ World Championship in Florida. He was already one of Hollywood’s biggest stars.McQueen and his teammate Peter Revson had indeed pulled off a heroic feat at the classic long-distance race in Florida. Although clearly outmatched in their Porsche 908/02 Spyder KH (Kurzheck or short tail), nicknamed “Flounder,” compared to the more powerful competition from the higher class, they led the pack in the final stages of the race and were only overtaken by Mario Andretti in a Ferrari on the final lap. The American driver crossed the finish line with a mere twenty-three-second gap after twelve hours at race pace.

Steve McQueen hated coming in second. He always wanted to win. But even for him, this second-place finish felt like a victory. A victory over himself, as it were; he had injured his left foot two weeks earlier at the motocross race at Lake Elsinore.

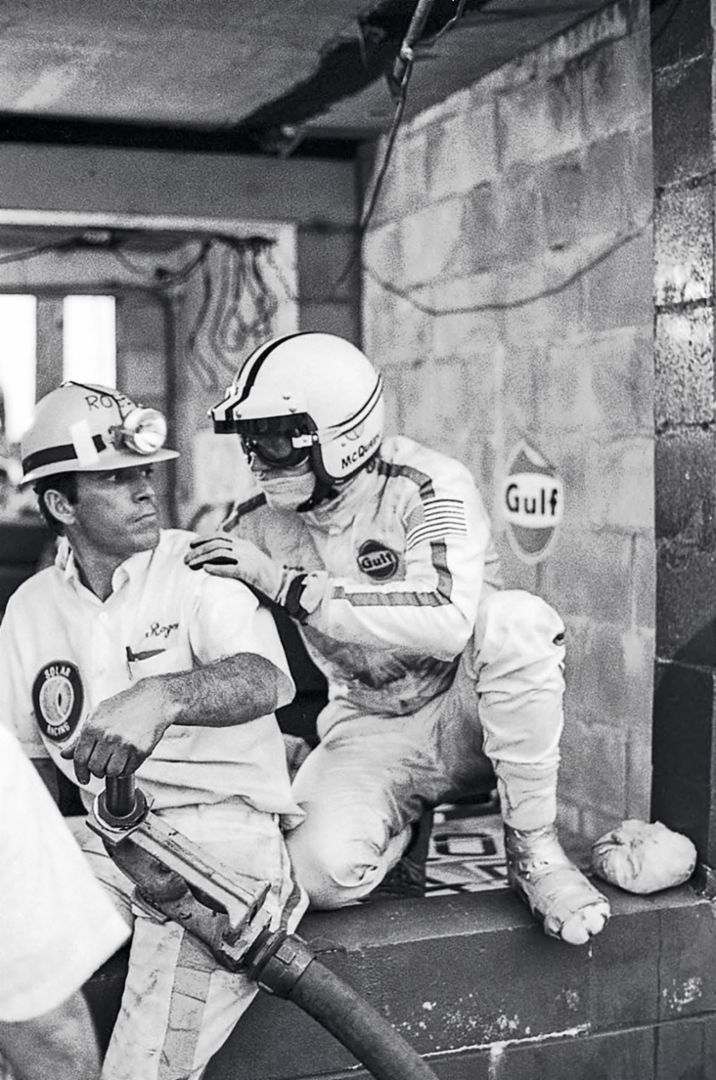

1970 Sebring

Racing break: McQueen waiting at the pit wall for his next stint in the twelve-hour race, while teammate Peter Revson was leading the pack in the 908/02. Not long before, McQueen had broken his left foot in several places during a motocross race. He showed up for Sebring with a slapdash cast. The King of Cool wouldn’t let even this painful injury put the brakes on his passion for racing.He had arrived for the race in Sebring on crutches and sporting a cast. “The foot’s broken in six places,” McQueen explained matter-of-factly to the waiting TV reporters. “We had to shorten the left pedal in the car and glue sandpaper to the sole of my shoe for me to be able to work the clutch.” The notion of pulling out, however, hadn’t crossed his mind. “I had given my word.”

That’s how he was. The coolest guy around. A guy who pushed boundaries and broke the rules. And not only in blockbusters like The Magnificent Seven, Bullitt, and The Towering Inferno—he was no different in real life. And that meant one thing above all others: racing. He was “always in a hurry,” Steve McQueen once said. “That’s how I live.” His son Chad, now fifty-nine, puts it this way: “He loved racing. It was his drug.”

He fled at top speed the poverty in which he had grown up in Missouri and Indiana. At the age of fourteen he was still living in a home for delinquent youths; as a seventeen-year-old, he enlisted in the Marines as a tank driver. At the age of twenty-two, he successfully auditioned for one of the coveted spots in Lee Strasberg’s famed Actors Studio in New York—the drama school par excellence in the 1950s.

“You only live once, so live life to the fullest.” Steve McQueen

To make ends meet, McQueen worked as a dishwasher and truck driver, and topped up his budget by running races on his Harley-Davidson. The prize money was usually one hundred dollars—a sizable sum at the time.

McQueen scored his first starring role at the age of twenty-seven in the science-fiction horror film The Blob. His pay: $3,000. It was the comparatively modest beginning of an unprecedented rise.

By the end of the 1950s, his income was sufficient to buy his first new car: a black Porsche 356 A Speedster. Like his fellow actor James Dean, McQueen felt drawn to the young brand out of Stuttgart. The Speedster and its 75 hp engine combined day-to-day usability with the qualities of a club racer.

In 1959 he entered nine races of the Sports Car Club of America in California. His very first official race, in Santa Barbara on May 31, ended with a victory in the novice class. “I was hooked. Racing gave me a new identity,” McQueen acknowledged later, “and it was important to me to have that independent identity.”

“I’m not sure that acting is something for a grown man to be doing.” Steve McQueen

Before the summer of 1959 drew to a close, McQueen had traded in the Speedster for a more powerful Porsche 356 A Carrera. Later he entered his first race in a pure race car, a Lotus Eleven. Countless more sports cars and racing machines would follow over the course of his twenty-year career. He collected almost obsessively—not only cars, but also motorcycles and even aircraft. “He was mad about speed and machines,” said Neile Adams, his first wife.

McQueen himself regarded his toys as a means of escape into another world in which only his laws applied. “I can really only relax when I’m racing. I loosen up at high speeds,” he once said in a television interview.

But there was something else as well: the need to assert himself, at any price. “He had to overtake you, that was his personality,” says Clifford Coleman, his assistant director for many years, who also raced motorcycles. “That’s why he was so successful. He had to win.”

And not only on the racetrack—also when it came to getting back his first Porsche 356 A Speedster. When McQueen found out that fellow race-car driver Bruce Meyer of Beverly Hills had bought the car for $1,500, he hounded him for months until Meyer let him have it back. McQueen would keep it for the rest of his life. “Today it would fetch a seven-figure sum,” says Meyer. “Not one million, several million.” Not that the Speedster with the rare central lock hubs is for sale. It’s firmly ensconced in Chad McQueen’s garage.

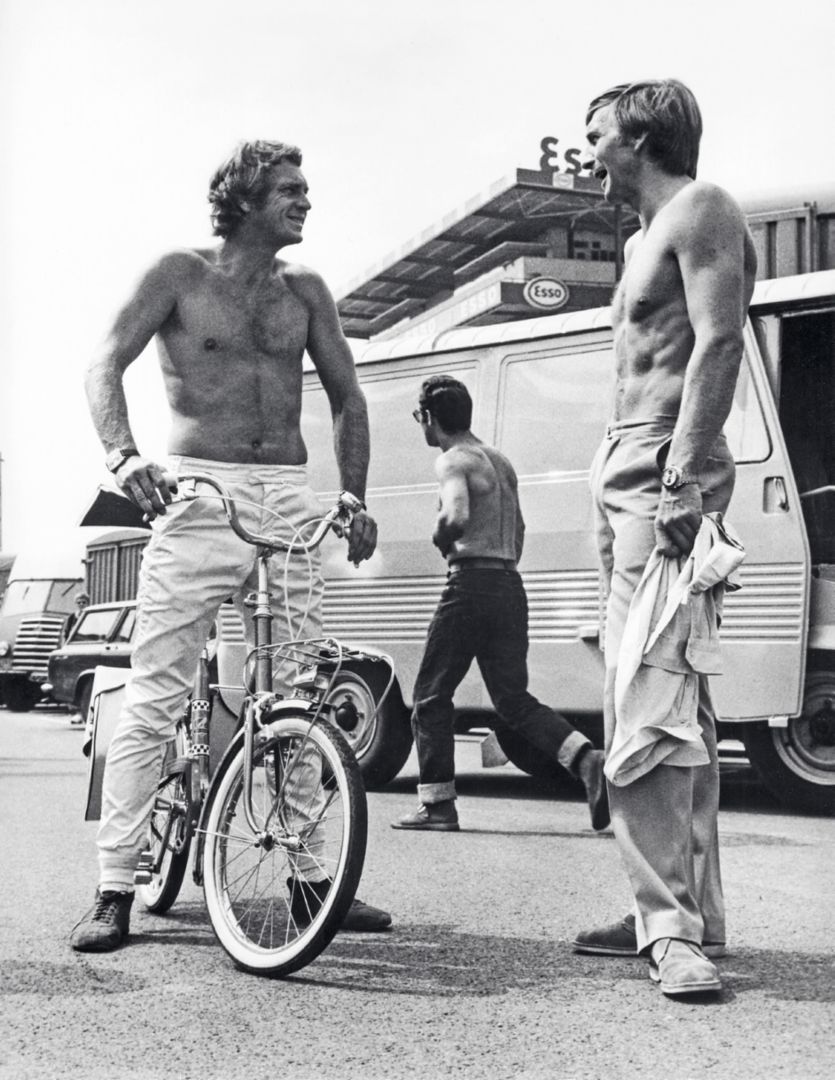

1970 Le Mans

Shooting break: McQueen enjoyed the camaraderie of the drivers and the unique opportunity to drive on the legendary track, even if not in competition. Filming the racing epic “Le Mans” was “almost an afterthought,” as Derek Bell (right) recalled later.Steve McQueen’s films, too, were made according to his rules. As one of the biggest film stars of the 1960s, he could do as he pleased. He built cars and motorcycles into the plot lines wherever possible. Take, for instance, the madcap beach drive with Faye Dunaway in a VW Buggy in The Thomas Crown Affair.

In the legendary chase scene in Bullitt he insisted on doing the stunts himself instead of using a double—a producer’s nightmare come true. An injured star would have meant losses to the tune of millions.

Yet even as he was filming one cinema hit after the other, he couldn’t resist continuing to take part in motocross races. Generally unnoticed by the public. McQueen enjoyed the anonymity granted to him by the helmet and entered races under the pseudonym Harvey Mushman. But even with a helmet on, his riding style was an unmistakable calling card. “He was strong and fast,” recalls assistant director Coleman. “That was evident in the way he rode a motorcycle—very aggressively.”

His racing activities on four wheels attracted somewhat more attention, not least because he occasionally shared the cockpit with world-class drivers like Innes Ireland, Pedro Rodríguez, and Stirling Moss. “He always wanted to measure himself against the best,” says son Chad.

McQueen was driving at the highest level by that time and even financed his own racing team through his company Solar Productions. The pinnacle of his racing career was to be the 12 Hours of Sebring on March 21, 1970, one of ten races in the World Sportscar Championship season.

The Porsche factory team brought seven cars to the starting line, including four 917 KH models, with which the team hoped to repeat the previous year’s world championship victory. But the lion’s share of attention went to McQueen and codriver Peter Revson, who were starting in the 908/02 as a private team. McQueen had already driven the open-cockpit car to victory in races in Holtville and Phoenix. Porsche driver Kurt Ahrens, who was trading places with Vic Elford at the wheel of a 917, kept a keen eye on his celebrity rival during training. “McQueen had a lot of talent, and he was ambitious, practically obsessed,” recalls the now eighty-year-old. “And he was fast, even if not quite as fast as Revson.”

1970 Sebring

Top showing: The McQueen/Revson duo earned the hard-won respect of established pros at the twelve-hour race. In the 908/02, they’d kept the more powerful competition at bay until just before the finish.With their 350 hp, three-liter Spyder, McQueen and his teammate didn’t stand a chance against the competition in the five-liter class with their roughly 600 hp—at least in theory. To compensate for their slower lap times, the team didn’t change tires or brake pads for the entire race. “We were all surprised how consistently they drove; the rigors of the race were considerable,” says Ahrens. “The track was made of concrete slabs; it gave us a good rattle.” McQueen also had the broken foot to contend with. But even that didn’t shake his composure. In the end, the pit strategy paid off with a sensational second place, notwithstanding McQueen and Revson benefiting from multiple dropouts and repairs suffered by competitors.

The best factory team Porsche, driven by Leo Kinnunen, Pedro Rodríguez, and Jo Siffert, came in fourth after a time-consuming pit stop. It was not the result Porsche had hoped for.

“Your finish enabled us to keep the lead in the Manufacturers’ World Championship, and for that I would like to thank you,” Ferry Porsche noted in his letter to McQueen.

“I look forward to meeting you personally at Le Mans.” Ferry Porsche

The head of Porsche and the Hollywood star were anticipating the high point in the annual racing calendar with equal enthusiasm. At the 24 Hours of Le Mans, McQueen intended to contest the race with Formula One champion Jackie Stewart in a Porsche 917. But, for insurance reasons, this would have caused him no end of trouble with the Hollywood brass.

For the first time in his life—or so it would seem—McQueen backed off and restricted himself to preparing for his racing epic Le Mans from trackside. He had the 908/02 from Sebring drive as a film car. Sharing driving duties, Herbert Linge and Jonathan Williams were to capture authentic racing scenes. In the end they took a respectable ninth place but were disqualified for a controversial rule violation.

For Porsche, the race would end with a long-awaited triumph: Hans Herrmann and Richard Attwood scored Porsche’s first overall victory at Le Mans in their red-and-white 917.

“He wanted to be one of us. And he was one of us.” Richard Attwood

1970 Sebring

Point of view: Only when racing, said the film star once, could he truly relax.Shortly thereafter, Steve McQueen started shooting the scenes for his film. He had long dreamed of making the ultimate movie about racing. Le Mans was his pet project. The film was on the verge of collapse several times, almost ruined him financially, and brought the end of his marriage to Neile Adams once and for all. He fired the first director, John Sturges, because the latter wanted to film a love story against the backdrop of the twenty-four-hour race. For McQueen, the race itself was the love story. The second director, Lee H. Katzin, finally gave way.

There never would be a coherent script and dialogue was scarce. Le Mans would only attain its cult status many years after its release in 1971.

For the driving scenes, McQueen brought in the top ranks of Le Mans professionals, including Derek Bell, the later five-time overall winner. It didn’t take long, Bell recalled later, before McQueen was roaring down the track himself in a 917. “Steve’s passion for speed was obvious: he wanted to drive full-throttle all the way.” The filming was “almost an afterthought” for McQueen, he said. “That’s probably why we all got along so well.” Richard Attwood, the winner in 1970, summed things up succinctly: “He wanted to be one of us. And he was one of us.”

Steve McQueen died of cancer at the young age of fifty on November 7, 1980.

INFO

Personality Rights of STEVE MCQUEEN are used with permission of Chadwick McQueen and The Terry McQueen Testamentary Trust. Represented exclusively by Greenlight.