Natural born winner

Porsche Great Britain: Whether racing in F1 or sports cars, Richard Attwood was no stranger to the winners’ podium. But perhaps the high point of his stellar career came in 1970, when, at the wheel of a 917 K, he helped give Porsche its very first Le Mans win.

Porsche at Le Mans

No other car maker has been more successful at the Le Mans 24 Hours than Porsche, which to date has achieved a record 19 wins. Trace that legacy back and you arrive at the 917, a fearsome race car that debuted in 1969. Capable of a still-astonishing 246mph at a time when aerodynamics were still not fully understood, the 917 was a flat-12-powered brute that even the best struggled to tame. Today, we’ve come to the Porsche Centre Silverstone to meet one of those who famously did.

Grand master

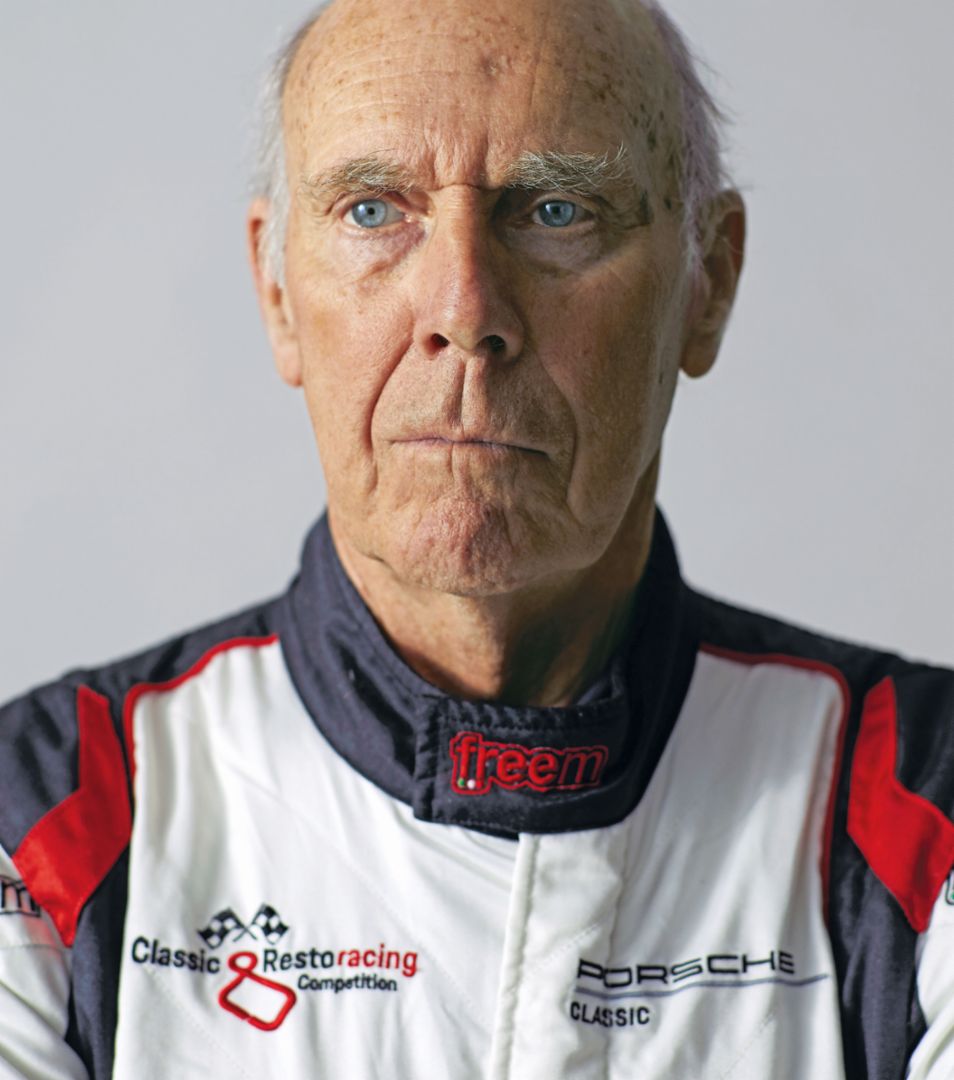

Now 78, Attwood still instructs twice a week at the Porsche Experience Centre, Silverstone.Born in the English city of Wolverhampton in 1940, Richard Attwood (with co-driver Hans Herrmann) drove the first Le Mans winner for Porsche in 1970 through the most atrocious of conditions. The 78-year-old Attwood, still slender and healthy, greets us at the front door of the Porsche Experience Centre at Silverstone, which has become his second home – indeed, he even instructs at the facility twice a week.

Attwood was 29 when he first drove a 917, but he’d already raced in Formula 1 and Formula 2, as well as sports cars. His potential well proven, Attwood was signed by Porsche for the 1969 World Sportscar Championship, which included Le Mans. First, he raced the eight-cylinder 908, but the factory team had already begun work on the 917 the previous year.

Bigger and faster

‘The 908 was probably good enough to win all the races in 1969,’ says Attwood. ‘But technical director Ferdinand Piech didn’t think that would be the case – he wanted something bigger and faster, particularly with victory at Le Mans in mind.’

Designed to meet the FIA’s new sports-prototype regulations, the 917 took the 908 as its starting point. The new car featured a lightweight spaceframe chassis into which Porsche fitted its largest-ever engine – a flat-12 created by joining two flat-sixes at the hip. The original bodywork included a detachable, longer rear deck, allowing two configurations.

‘I remember first seeing the 917 on a plinth at the Geneva show,’ remembers Attwood. ‘Even static, it looked like a monster.’ And so it proved when it was driven in anger. Attwood believes German Formula 1 and sports-car driver Gerhard Mitter blew his engine to avoid driving it in the wet on its debut at Spa, and remembers that none of the factory drivers wanted to drive it at the Nürburgring. ‘It was almost like a strike. I didn’t want to drive it either!’ he adds.

But when Vic Elford requested Attwood as his co-driver for Le Mans in 1969, he could avoid the 917 no longer. Further adding to his apprehension, Attwood wasn’t able to drive the 917 before practice.

‘Vic said he liked the 917 – I don’t know if it was out of bravado or something. But as soon as I drove it, it wandered horrendously,’ says Attwood. ‘The testing had been done on an airstrip, and I don’t believe they could’ve been getting to the terminal velocity – maybe 185mph, but it could do 235mph. There was a clue something wasn’t right from the start: if you looked in the mirror in the pits, you got a very good view behind, but on the Mulsanne Straight, you couldn’t see a thing!’

Long and short of it

Attwood favoured the 917 Shorttail over the Longtail, due to its extra aerodynamic stability.The 917’s fearsome reputation was cemented at that Le Mans, when the experienced Digby Martland refused to race after a high-speed spin in the build-up to the race. Martland’s reluctance proved well founded when his co-driver, privateer John Woolfe, was tragically killed after losing control on the first lap.

Battling through the night

The race continued. Elford drove the first double stint of around 100 minutes, Attwood swapping into the 917’s cockpit for the same length of time when he pitted. He remembers having to make constant corrections to the steering, which was light and vague, because the nose was lifting. He also recalls the unbearable noise from the exhaust outlets – two exiting under each door, two at the back – and how he would rest his head against the bulkhead because his neck became so sore.

‘I was in a lot of pain after less than two hours,’ Attwood grimaces. ‘Fortunately, the race was dry, because, in the wet, I honestly believe we would’ve retired the car.’ Yet, somehow, the two drivers wrestled the car through the night, finding themselves with a six-lap lead after 21 hours. It was only a gearbox failure that forced retirement. ‘The factory thought I was disappointed at retiring, but I was just utterly drained and actually relieved!’ laughs Attwood.

“I didn’t think we stood a chance, even in the wet… When I got back to the garage, I was staggered to learn we were leading.” Richard Attwood

Moment of history

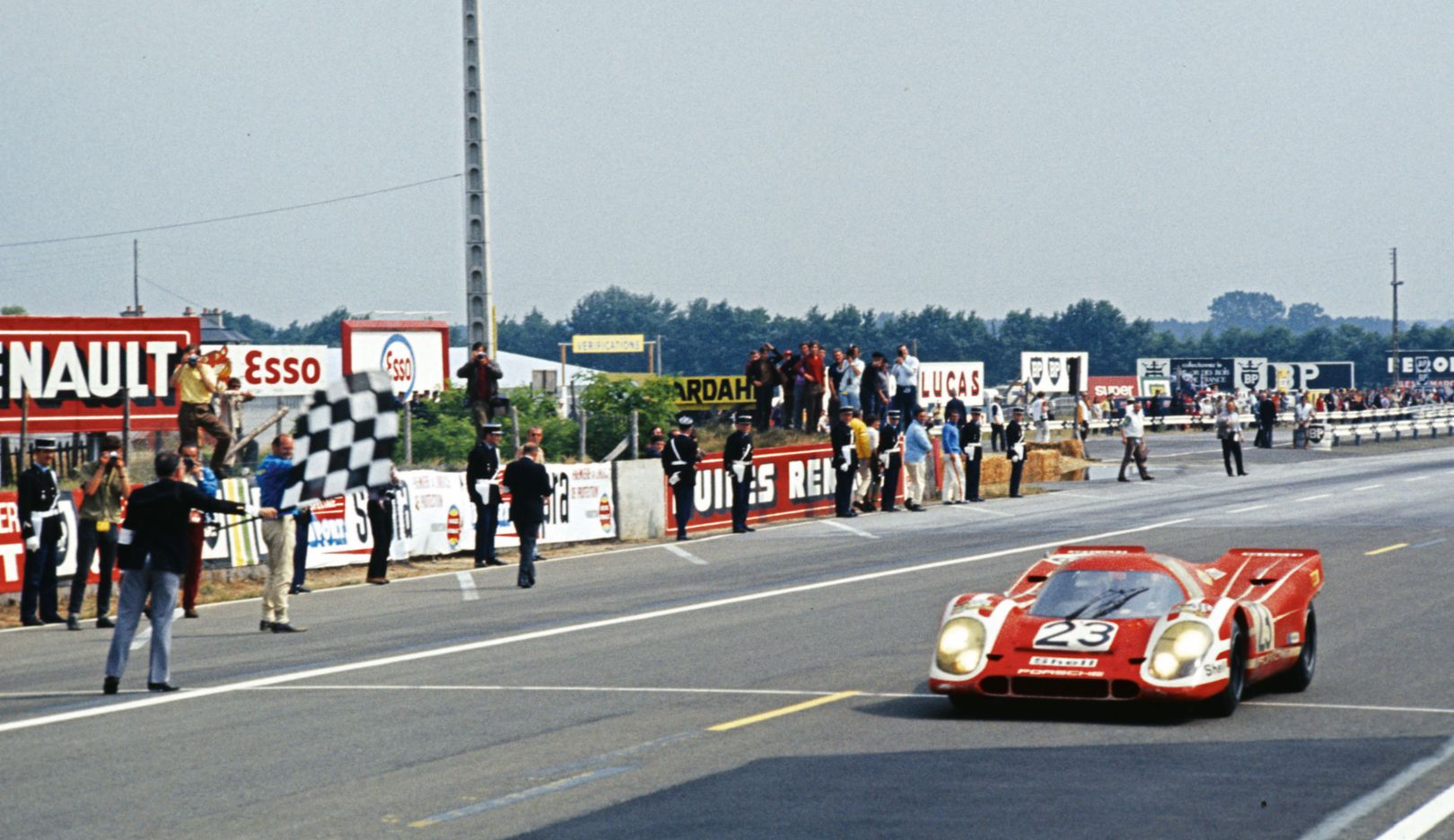

14 June 1970: the Porsche Salzburg 917 K takes the chequered flag at Le Mans, giving the marque its first Le Mans victory.Over the winter, Porsche worked hard to cure the 917’s handling maladies, in partnership with John Wyer and his JWA Gulf Team. Lead engineer John Horsman was instrumental in the fabrication of the experimental aluminium sheets fitted to the rear of the car. This more upswept tail was an instant success, and the mock-up ultimately informed the 917 K – the K standing for Kurzheck or Shorttail. ‘The Shorttail wasn’t as fast in a straight line, but you had the stability,’ recalls Attwood. ‘It was like driving a completely different car – we had to slow down for the kink at the end of the straight the year before, but now it was flat – piece of cake.’

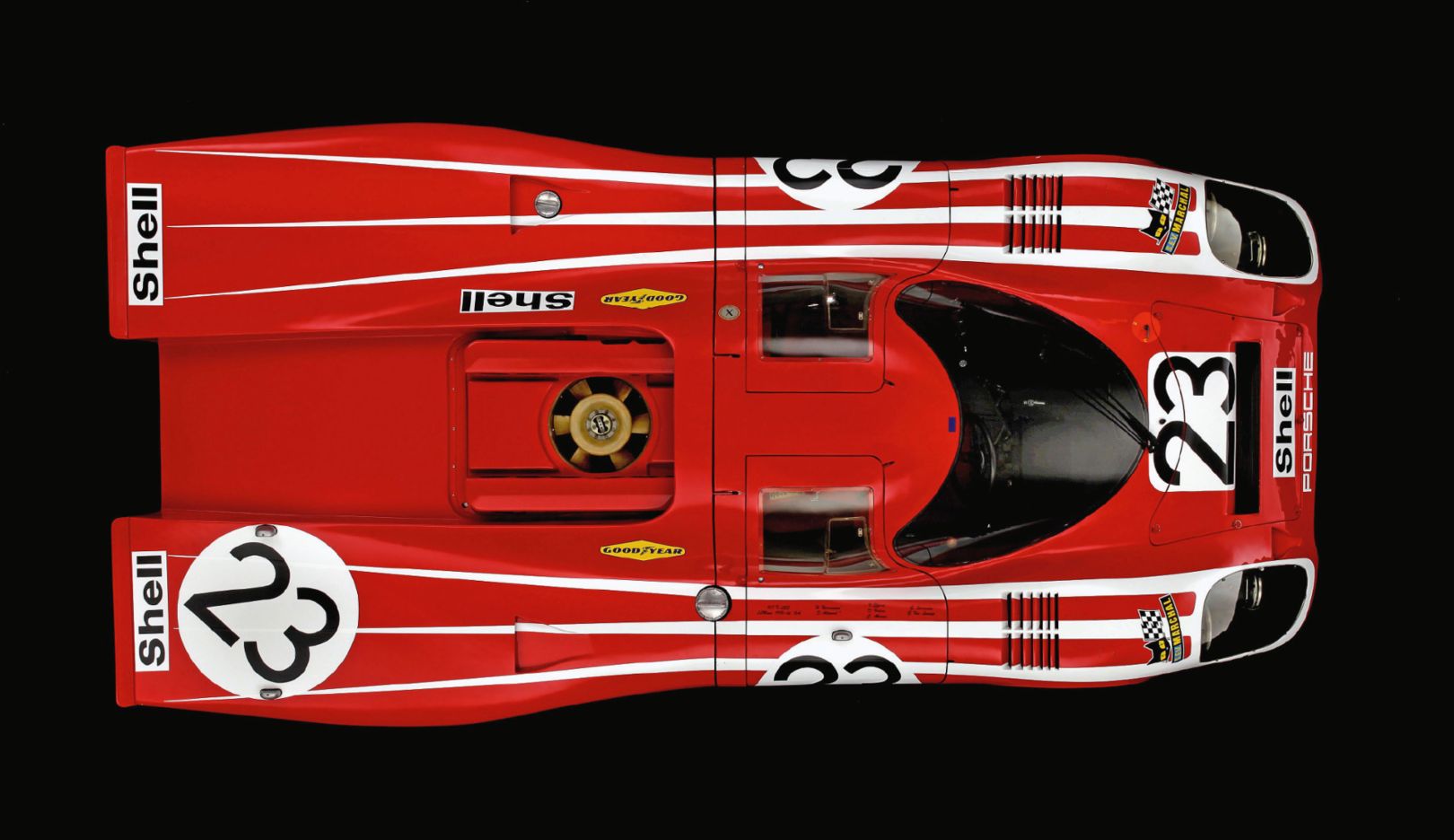

Three distinct Porsche-backed teams were entered in 1970: the JWA Team, Martini Racing, and Porsche Salzburg, to which Attwood was contracted. Both Longtail and Shorttail 917s were available, and the flat-12 had grown from 4.5 litres to 4.9 and then 5.0 litres. With over 630bhp to the 4.5’s 500bhp, a 5.0-litre Longtail seemed the obvious choice to do battle with the Ferrari 512s on Le Mans’ high-speed straights.

Not for Attwood, though. ‘I preferred the stability of the Shorttail, and we’d had problems with the gearbox the previous year, so I thought, “Why put more stress through it with a bigger engine?” I asked for the 4.5.’ Complementing this measured approach, Hans Herrmann would be Attwood’s co-driver – ‘a steady guy who’d raced a long time’.

When it came to qualifying for the 1970 race, however, the pair quickly began to rue their configuration. ‘We qualified 15th. I didn’t think we stood a chance, even in the wet,’ says the first Porsche Le Mans winner.

But, watching from the pit wall, Attwood could barely believe his eyes as Herrmann drove the first race stint: ‘Le Mans really was an endurance test more than a race back then, but it was like watching GP cars at the start, with everyone jostling, trying to fight already.’

The rate of attrition was high, even before the rain came – ‘three Ferraris went out in one go, I thought people were being so silly’ – and then the heavens opened. ‘There was a lot of rain through the night and into the next day. It was one of the wettest races ever – you’d have pace cars and probably red flags today.’

Hard to handle

Good for 246mph, the 917 was initially tricky to control – a problem cured by new rear bodywork.

Red, white and fast

Attwood and Hans Herrmann raced for the Porsche Salzburg team in its distinctive red-and-white livery.Total faith

One by one, key rivals either fell victim to the conditions or succumbed to technical gremlins: Mike Hailwood and David Hobbs had been favourite to win, but their 917 slithered off the track; Pedro Rodriguez and Leo Kinnunen, also in a 917, saw their challenge ended by cooling-fan problems. Attwood, meanwhile, wasn’t functioning perfectly himself.

‘I had mumps, and was sustaining myself purely with milk, maybe a banana – anything that didn’t have much taste. When I wasn’t driving, I just wanted to rest, so, when I got back to the garage, I was staggered to learn that we were leading.’

In second place was a Martin Racing 917 Longtail, and the team had ordered drivers Gérard Larrousse and Willi Kauhsen to take it easy after 14 hours of racing. Danger still lurked on the sodden circuit, however. ‘It sounds simple to circulate at reduced speed, but it’s easy to lose concentration for a fraction – and then you’re gone,’ explains Attwood. ‘We were also having problems due to the conditions – the electronics were soaked and the car was starting to misfire, so I had to keep the engine revs up. There was a lot of aquaplaning and I had a wobble coming out of the esses. It was all quite fraught, but I felt I was going so slowly.’

Attwood maintained the lead, however, handing over to Herrmann to take the final stint. ‘I had total faith, and he was much more desperate to win than me.’ With the team on tenterhooks in the pits, Herrmann kept up the consistency to cross the finishing line first, defying the expectations of 24 hours earlier. Only seven cars were classified.

Absolute power:

The 917’s flat-12 engine was so large, drivers had to be pushed forward in the cockpit – in fact, their feet were positioned ahead of the front axle.At last, Porsche had won Le Mans outright. The team were ecstatic, but elation took some time to sink in for Attwood. ‘We had a shambles of a celebration, where we were stuck on the back of a pick-up truck and paraded around in the wet. I was thinking, “Oh no, we’re doing a full lap,” but we turned back, thank God,’ he laughs. ‘I remember that we went out to dinner afterwards to celebrate, but feeling an absolute wimp and having to leave after 30 minutes!’ More fitting celebrations came later, when both the first- and second-placed 917s were paraded through Stuttgart.

Herrmann retired after the race, honouring a promise to his wife. At the 1971 Le Mans, Attwood finished second in a 917 (while Helmut Marko and Gijs van Lennep claimed a second consecutive victory for the car), and retired later that season. A rule-change outlawed the 917 for 1972, and it evolved to tackle the Can-Am series – with even greater success.

Attwood still catches up with Herrmann a couple of times a year, and his association with Porsche remains strong. Not only does he enjoy instructing at the Porsche Experience Centre, Silverstone, but he’s recently raced Project 70 – a historic 911 built to celebrate the 70th anniversary of Porsche sports cars. In the build-up to a recent race at Donington, co-driver Anthony Reid accidentally over-revved the engine and broke a rocker in the valvetrain. ‘The guy running the team said he’d fit a stronger replacement,’ says Attwood, ‘but I said, “Just replace the rocker like for like – it’s a release valve. Better the rocker breaks than something more serious goes.’

He might have raced and won in one of the fastest race cars of all time, but, almost half a century on, Richard Attwood still understands it isn’t all about brute force.