The Golden Middle

The equator divides the earth into north and south—as it does Ecuador. A journey through the land that bears its name.

Consumption data

911 Carrera Cabriolet

Fuel consumption combined: 9.6 l/100 km

CO2 emissions combined: 218 g/km

911 Carrera

Fuel consumption combined: 9.4 l/100 km

CO2 emissions combined: 215 g/km

911 Carrera S

Fuel consumption combined: 10.0 – 9.6 l/100 km

CO2 emissions combined: 227 – 220 g/km

(as of 07/2020)

The sea is wild, the sky is gray, and the temperature is 25 degrees Celsius. But it’s only six in the morning. In half an hour the sun will rise for the race to its zenith, burning with the strongest UV radiation on earth, before descending again precisely twelve hours later.

0 meters above sea level, 0 degrees latitude, 0 kilometers/distance

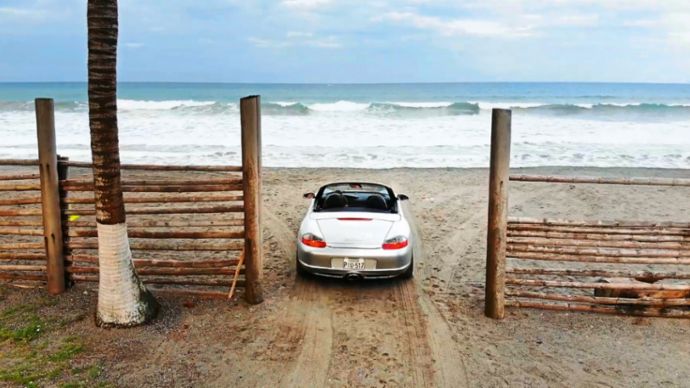

The silver-gray Boxster is in Pedernales, a town on the coast of the Pacific Ocean. The engine is idling. Andrés Galardo is at the wheel with his girlfriend, María Caridad, sitting by his side. The roof is open, and the spoiler is retracted. A small camera drone whizzes above the roadster. It’s the beginning of a journey across one of the least known and most fascinating countries in northwestern South America: Ecuador.

Starting point:

The Pacific coast near Pedernales. This is where the equator meets Ecuador. One hundred kilometers later, the road passes through the woods as it ascends into the Andes.

Quito, the capital, is around three hundred kilometers and 2,850 meters of elevation away. Galardo came down from there the evening before. It was already dark when he arrived, with hungry mosquitoes buzzing around the pool. The hotel proprietor warned against parking under the palms: beware of coconuts. Now the Porsche drives off, with the sound of 228 hp confidently rising above the ceaseless roar of the surf. The Boxster was built in 2003 and bought by Galardo seven years later. Ever since he first rode in his uncle Mario’s 911 Turbo (Type 930) as a kid, he dreamed of owning his own Porsche. He started saving up. At the tender age of twenty-six he had enough money saved to purchase the Boxster.

He accelerates. Alas, on the road to Pedernales, a small city just a few kilometers north of the equator, the speed limit is an unsatisfying 100 kmh. Indeed, it’s not permitted to drive faster anywhere in Ecuador—not even on the many new eight-lane highways. If the offerings of the road system in Ecuador are generous, its official speed-minders are anything but: zero tolerance is the policy here. Even speeds barely above the

100 kmh limit can result in sizable fines. So Galardo applies the brakes almost as soon as he starts speeding up. He’s still in the Costa, the fertile lowlands along the coast and the country’s fourth geographic region, alongside the Andean Highlands, the Amazon basin, and the Galápagos Islands.

Pit stop:

Six dollars buys a full menu—and a view of the mountain stream is included free of charge.

In the middle of the world, spectacularly distinct landscapes are often just a few minutes’ drive away from each other.

The road rises gently as it wends its way through plantations and bamboo forests. Here and there, mechanical diggers burrow their way deep into the ground: El Dorado beckons. Gold diggers are in search of what they hope will make them rich and powerful. At the moment they’re still working for the standard minimum wage of US$386 a month. In 2000 Ecuador abandoned its national currency, the sucre, and replaced it with the U.S. dollar. The move has made it easier to export oil, bananas, and cut flowers—not to mention the country’s biodiversity, which could prove a winning business model. Ecuador, after all, boasts the highest biodiversity in the world relative to its size. On the Galápagos Islands: giant tortoises, lizards, sea lions. Off the mainland coast from June through September: thousands of mating humpback whales. Along the coast: iguanas, parrots, and monkeys. In the highlands: condors and vicuñas, the largest birds of prey and smallest camels in the world, respectively. And in the Amazon basin on the other side of the mountains: tapirs, jaguars, parrots, piranhas, and more insect species than in all of Europe.

1,500 meters above sea level, 0 degrees latitude, 200 kilometers/distance

The provincial town of Mindo lies below. Ahead of the Boxster, cars back up behind a landslide. The road is blocked, and the air is thick with fog. Dense clouds are ensnared by the jungle on the western edge of the Andes. It’s raining. Waterfalls thunder in the distance. Visibility is less than fifty meters. Galardo is the designer, product manager, and co-owner of a motorcycle factory. Every year he thinks up a new model, flies to China, buys parts, and builds roughly a thousand motorcycles that top out at 350 cc. The bestsellers are enduros, for tracks off the main roads. Chickens, pigs, the weekly shopping, entire families—here, almost everything is transported by motorcycle. Even most police in Ecuador ply their trade on motos. There are few police cruisers on patrol. The traffic jam slowly begins to untangle. A few hundred switchbacks later, Quito swings into view.

The highest capital in the world is not too far from the coconut-strewn beaches of the west coast.

2,850 meters above sea level, 0 degrees latitude, 287 kilometers/distance

Nice and cool:

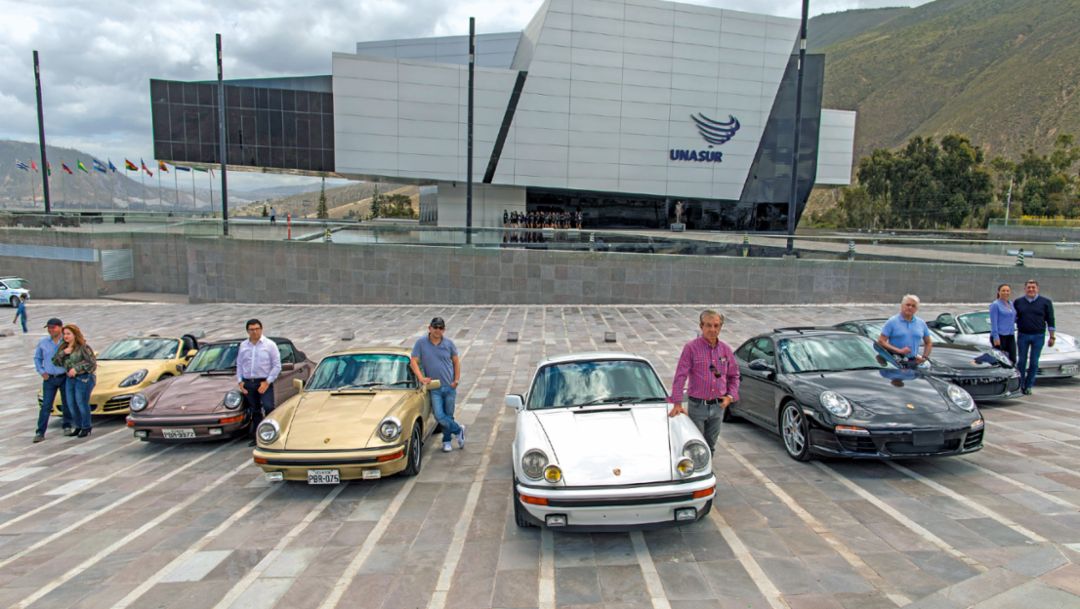

At 2,850 meters above sea level, Quito is nearly on the equator. In other words, expect shortness of breath—and you might want to check the oil level again.The highest capital in the world has 1.5 million inhabitants and thin air—which means heavy breathing for lowlanders—and is Ecuador’s most beautiful city. Cool summer air, steep cobblestone roads, colonial architecture, luxury hotels, coffee shops, ice cream vendors. Galardo has made a beeline to a gas station in the suburb of Cumbayá, where Porsche enthusiasts like to gather. Felipe Otero is there with his wife, kids, and panama hat in a red

911 Targa from the year 1977. Patricio Verduso and his wife, Alexandra, drive a golden 911 Cabriolet. Diego Guayasamin arrives with his girlfriend Natalie in a black 911 Carrera.

Jean-Pierre Michelet drives a black 911 from 1974. His daughter Dominique has come along. She loves riding in the Porsche with Papa. Michelet is a celebrity in Ecuador: he was a race-car driver like his father, Pascal, and took second place in his class at the 1995 running of the 24 Hours of Daytona. Today he hosts Sinfonía de Motores, one of the most popular TV sports shows, after soccer broadcasts of course. Michelet has loved Porsches since childhood. “You know how to drive this 911?” he asks. “With your bum. You have to feel everything and brake in good time before the corner.”

4,658 meters above sea level, 0°41´3˝ S latitude, 370 kilometers/distance

Highlight:

The active volcano Cotopaxi is just sixty kilometers from Quito. Whenever it erupts, it rains ash over the capital.The Porsche convoy rumbles down this section of the Panamericana at 100 kmh. To the left, Cotopaxi towers over the landscape, its snow-capped summit reaching 5,897 meters into the azure sky. There’s little to suggest that the mountain is among the most active and dangerous volcanoes in the world, notwithstanding the green evacuation route signs within and outside of Quito. It has erupted some fifty times over the past three hundred years. At the foot of the mountain, the city of Latacunga has been completely destroyed and rebuilt twice.

Just outside of Latacunga, the sports cars turn off onto a new asphalt road that corkscrews its way up to the four-thousand-meter point. Vicuñas graze on the sparse highlands. Diego Aguirre, a car dealer, cranks up the stereo in his 911 Carrera S and Jamiroquai’s “White Knuckle Ride” pours out of the speakers. He’s put together a soundtrack especially for this trip. After a dozen kilometers, a “sleeping policeman,” as speed bumps are also known in Ecuador, stops the caravan of Porsches. Past it lies an impassable washboard of a road. So it’s back to the plateau. Aguirre plays Frank Sinatra’s “My Way.” Night has fallen by the time the group returns to Quito. Just one last jaunt up to the statue of the Madonna on El Panecillo, which translates as “bread roll” and is perched 3,035 meters above sea level. So the Spaniards named it, at any rate. The Incas called it Shungoloma—the “heart hill.” Bejeweled with a thousand lights, the view of the Ecuadorean capital nestled between mountain silhouettes is breathtaking.

1,900 meters above sea level, 0°44´9˝ S latitude, 550 kilometers/distance

A journey through the breathtaking landscape of Ecuador.

In the east, the Amazon basin and its evergreen rain forest stretch out over more than half of the country’s area.

Back down again. The Amazon basin. The primeval forest. The Río Victoria cuts deep into the bedrock. Waterfalls plunge into the depths from the opposing cliff. Fog rises from the peaks. The Andes have been crossed. Now the sports-car convoy is in the country’s wild east, driving down to the roadblock in Baeza. Special police units have set up a checkpoint. A traffic jam forms. The Porsche drivers aren’t interested in waiting. They turn around.

2,850 meters above sea level, 0 degrees latitude, 650 kilometers/distance

Running north to south, the Andes span the country like a longitudinal axis to the equator.

Back in Quito, the parade of Porsches proceeds down the new city motorway toward Mitad del Mundo, the equator monument north of the city, in San Antonio de Pichincha. They park in front of the UNASUR building, the futuristic seat of the Union of South American Nations designed by Diego Guayasamin. UNASUR’s chief of protocol welcomes the group.

End of the excursion:

Diego Guayasamin (right) designed the UNASUR building. The Porsche community enjoys the perks.His office, entirely cased in glass extending fifty unsupported meters toward the southern hemisphere, lies on the equator. A bold act of structural defiance in this earthquake-prone region. On the horizon, a snow-capped volcano soars above the mountain ranges surrounding the city. The air is clear. From this perspective, the sweltering coast they set out from three days ago might as well be in a different world. The chief of protocol sends off each member of the group with a book from his organization: Where Dreams Are Born. It’s about how children conquer the world and can shape it for the future.