Amazing Save!

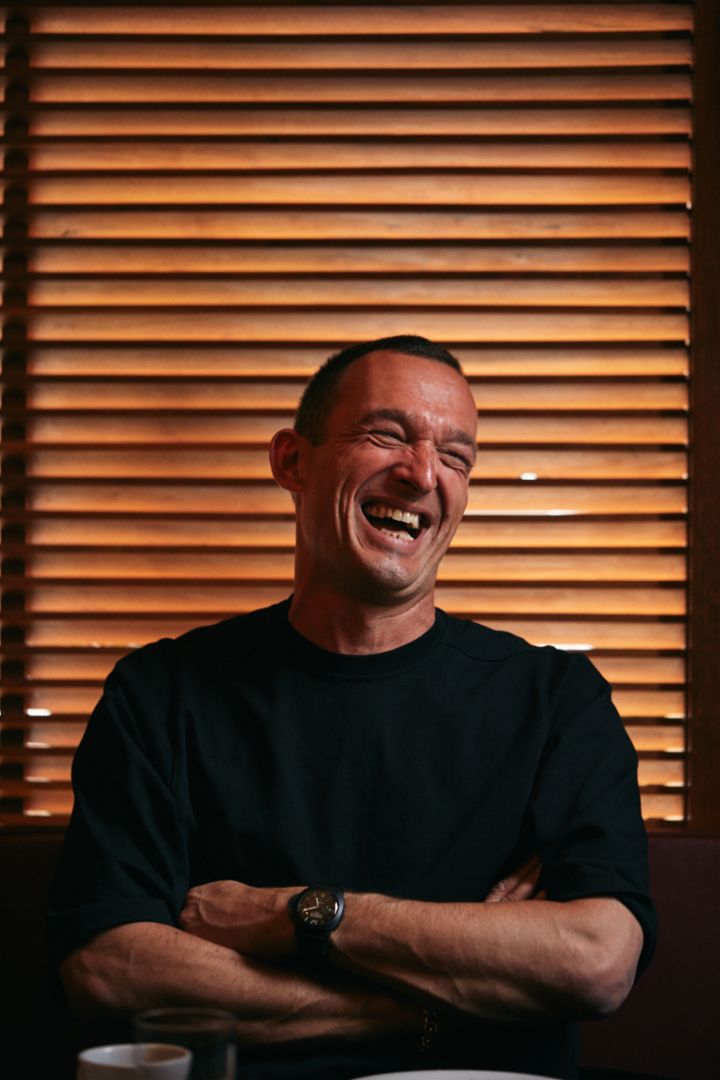

Albert Ostermaier is a dramatist, goalkeeper on the German writers’ national soccer team and a passionate 911 driver. Where does writer’s passion for soccer come from and what role does movement play in his life? An encounter between the posts.

A photoshoot on the neighborhood soccer field on a spring day in Munich. Albert Ostermaier stands on the goal line and points to the bottom right corner: That’s where he wants the ball, a hand’s width above the grass, twenty centimeters to the right of the goalpost. “But shoot with pace,” says the keeper to the shooter as he crouches into position. He can’t go down in slow motion, after all. And he wouldn’t want to even if he could. Slowly descending to the ball, nice and gently? Are you kidding?

Ostermaier is a writer, goalkeeper of the German writers’ national soccer team and the owner of a 911 Carrera Cabriolet, model year 1998. He published his first volume of poems at the tender age of 20. A good dozen others would follow, along with three novels, four libretti for the opera and 24 plays. The 50-year-old, whom critics celebrate as a writer who “raises the temperature of language,” a man whose works dare to risk the grandiose in tone and gesture, is regarded as one of the most important contemporary German dramatists. His works continue to be staged in many great theaters. As a small boy, he visited the training camp of FC Bayern München. Sepp Maier gave him a jersey and gloves as a gift. He’s been a fervent FCB fan ever since, and of course he wanted to grow up to be a great goalkeeper as well. His father thought that was nonsense and didn’t let him train with a club. Ostermaier then used his free time to kick a ball around, and deep down, he remained true to his dream. And the German writers’ national soccer team ultimately saw it come true.

The Autonama is a team formed by novelists, poets and playwrights. Supported by the German Football Association Culture Foundation, they’ve been lacing up the boots against other teams of artists and literati from around the world in the Writers’ League and the Wor(l)d Cup of writers at irregular intervals since 2005 – sport, cultural exchange and intercultural understanding in one. In 2010, the team reached the final of the author’s European championship against Turkey in Unna. Ostermaier kept his nerve in the decisive penalty shootout – Autonama became the European champions. “Better than the Nobel prize for literature!” as he exclaimed ecstatically into the cameras.

The goalkeeper, says Ostermaier, leads a paradoxical existence: Standing at the back, imploring the team in front not to let the opponent through. Yet at the same time, always waiting and hoping for the chance to make a brilliant save. But woe betide the netminder who makes a mistake.

A fusillade of scornful whistles rains down, and the mind begins to play tricks. What if the next shot isn’t parried either?

The players between the posts have to look for risks, and yet always keep their nerve. They want to be the best, with an intense focus and sometimes excessive ambition that can go beyond the call of duty. In the World Cup semifinals in 1982, German goalkeeper Toni Schuhmacher rammed into Frenchman Patrick Battiston with a full-speed body-check. The French back was knocked unconscious, suffered spinal injuries and lost two teeth.

On the other hand there are the unbelievable reflexes, the daredevil saves, the decisive flashes of glory. A goalkeeper is always there where the outcome is decided. A rock solid rampart defying all attacks. Albert Ostermaier poured it all into a poem, “Ode to Kahn.” Tirelessly jeered by banana-lobbing opposing fans, the former FC Bayern netminder is mythologized in the poem that honors him. When he flies through the air, “it’s as if for just a moment/if only he could tarry in it/he would punch the sun out of its orbit”.

Yet agility and power are the result of hard work. A goalkeeper trains again and again, with a stubborn resolve – which is what makes him resemble the writer, says Ostermaier. “My sentences come from the subconscious; I have to free them. That only works if I train my language, repeat, practice.” That’s why he’s a disciplined worker: He’s at his desk writing by eight in the morning at the latest, and writes till the late mid-afternoon.

The 911 has its place in this life as well: “I value the car because it’s so pure and clear. I change when I sit in it; I forget myself. My thoughts flow, like the scenes in a road movie. Poems have their own sound, a speed and rhythm. I love being in motion because motion is a poetic state. While driving, the engine of fantasy joins forces with the engine of the car.

The ball comes. Ostermaier leaps, extends, flies. He wants to get it, but misses it by a centimeter and lands on the lush green turf with a jolt. He smiles. “I’ll get the next one.” He once wrote a line about French Nobel laureate and recreational netminder Albert Camus that provides a perfect descriptions of himself at this moment: “One may imagine Camus as a happy goaltender.”

Albert Ostermaier

The Munich-based writer is best known as a poet and playwright. His plays have been staged by many illustrious directors, including Andrea Breth and Martin Kušej. His latest novel, Lenz im Libanon [Lenz in Lebanon] was published by Suhrkamp Verlag in 2015. Albert Ostermaier has received numerous major prizes and awards, including the Kleist Prize, the Bertolt Brecht Prize and the Welt literature prize for his complete oeuvre of literary work.

In his 2012 novella Die Liebende [The Lover], a Porsche 911 earns a mention. His latest work, Die verlorene Oper. Ruhrepos [The Lost Opera: Ruhr Epic] premiered at the 2018 Ruhrfestspiele in Recklinghausen in a collaboration with the Staatsschauspiel Hannover theatre.

More information: www.albert-ostermaier.com