Take Two

More than a mere race car, it was one of the camera cars for the movie The Speed Merchants. Lost for years, it was tracked down, saved from the junkyard, and restored. Christophorus presents the rich history of a 911 ST 2.5.

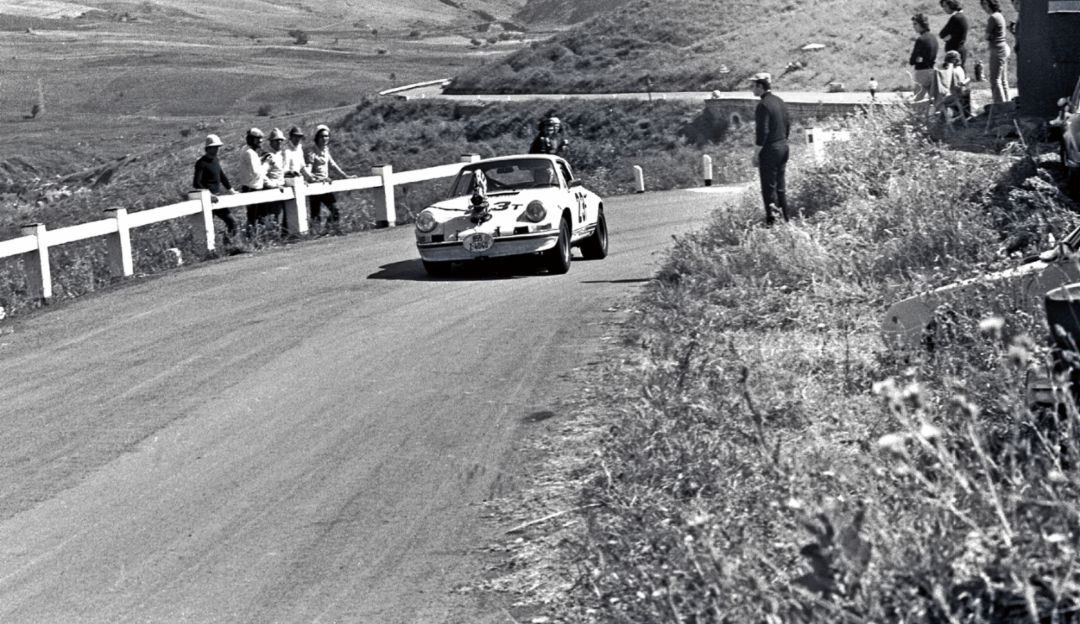

The deep voice of British race-car driver Vic Elford provides the commentary for a hit video on YouTube. The viewer flies at breakneck speed along a stretch of the legendary Targa Florio, with the camera just a few centimeters above the ground. It was the summer of 1972, and top members of the motorsports community were practicing for the famous sports-car race through the Madonie mountains of Sicily. Elford had already won the contest in 1968 with a Porsche 907. A former rally driver and winner of Monte Carlo, he knew nearly every tree and bump in the road. The clip that he narrates was filmed by a 16-mm Arriflex camera mounted to the hood of a yellow Porsche 911 S. At the wheel was cameraman Michael Keyser, an American who had entered various Porsche 911s in U.S. races as a private driver in previous years.

Keyser met Jürgen Barth on a visit to Zuffenhausen in December of 1971 to inspect progress on his special-order GT race car. Both were twenty-four years old at the time. The son of race-car driver Edgar Barth was working for the Porsche press department and had recently launched a career in motorsports that would culminate in an overall victory at Le Mans in 1977. Keyser, who would later achieve fame with the book A French Kiss with Death about the highs and lows of making the film Le Mans with Steve McQueen, persuaded Barth to join his European adventure as the second driver and cameraman. He was planning a special project, namely, a documentary about the 1972 World Sportscar Championship. The title was already set: The Speed Merchants.

Keyser had lined up a big team to shoot dramatic material for the movie on and with the 911 on the track. Highlights were to include high-speed sequences from the Targa Florio. “About halfway through the stretch, I was overtaken by Rolf Stommelen,” Keyser recalls. “Much to my delight, he didn’t just zoom past. Instead, he dallied in front of us to give us some really good shots. Then he waved, stepped on the gas, and vanished from sight a few curves later.” Unfortunately, when the footage was examined a few months later, it turned out that a lot of it was unusable. “Shortly after Stommelen raced off, a large beetle found its death on the lens, which tinted the whole thing dark red,” says Keyser.

Spectacular transport

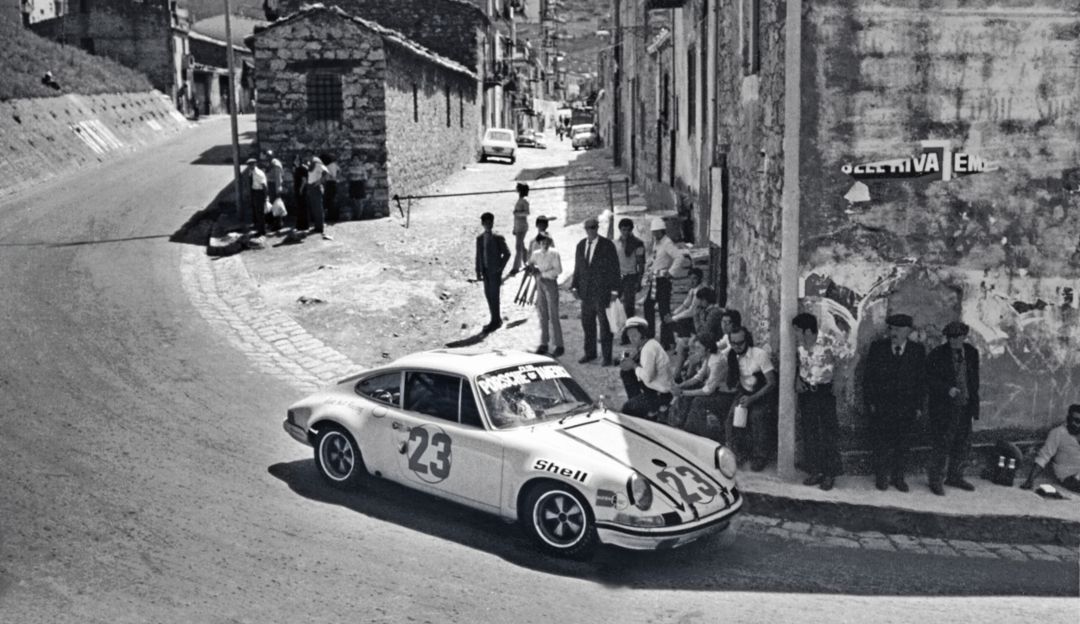

The 911 ST 2.5 with chassis number 230 0538 appears only for a few seconds in The Speed Merchants, but it made a splash that extended well past the 1972 season. The Porsche was one of a final series of twenty-four 911s modified for racing customers. It didn’t yet have the ducktail or tray-shaped spoiler of the subsequent RS, RSR, and Turbo models. A type 911/70 with a 270-hp, 2.5-liter boxer engine and a price tag of 49,680 Deutsch marks, it was the latest achievement in a technical trajectory that had begun in 1965 with an approximately 130-hp 911 2.0 at the Monte Carlo Rally.

Barth and Keyser’s adventure started at the 12 Hours of Sebring. Their race on the bumpy airfield circuit in Florida ended with a technical problem when the countershaft for the camshaft’s chain drive broke. The Porsche was loaded onto a truck and transported across the Atlantic by boat. Its first stop in Europe was Reutlingen, where Keyser’s team was using Max Moritz’s workshop as a base. The team then set off for the Targa Florio. “A heavily loaded truck with an automatic transmission is not the ideal vehicle for crossing the Alps to Italy,” noted Keyser in his journal. “The brakes were in danger of overheating, so our driver and head mechanic Hans Mandt was constantly ready to leap out of the cabin, since there wasn’t any run-off space.” But the Porsche eventually arrived in Sicily in good shape. During the race, Barth and Keyser were in sixth place overall until the eighth lap, when Barth skidded on oil and hit a wall. “Fortunately neither the oil cooler nor the suspension was damaged. But the time we spent straightening everything in the pit knocked us back to tenth place,” recalls Barth.

“I was extremely queasy. But I quickly recovered once I gave the wheel to Jürgen and felt solid ground under my feet again. The most important thing was that the car was still in one piece.” Michael KEYSER

Just one week later they entered the one-thousand-kilometer race on the Nürburgring. This time there weren’t any cameras, because the German automobile club ADAC had banned them following an incident when a camera broke off at high speed. From a starting place of twenty-ninth, the duo worked their way up to thirteenth, which was enough for fourth place in the GT class. Keyser found the Nordschleife less difficult to learn than the Targa Florio course; nevertheless, the “Green Hell” was daunting. “I was extremely queasy—probably as a result of some sausage I had just eaten, plus the constant up and down of the course. But I quickly recovered once I gave the wheel to Jürgen and felt solid ground under my feet again. Anyway, the most important thing was that the car was still in one piece.” At Le Mans, the season’s highlight, the Porsche was again used as a camera car.

Action!

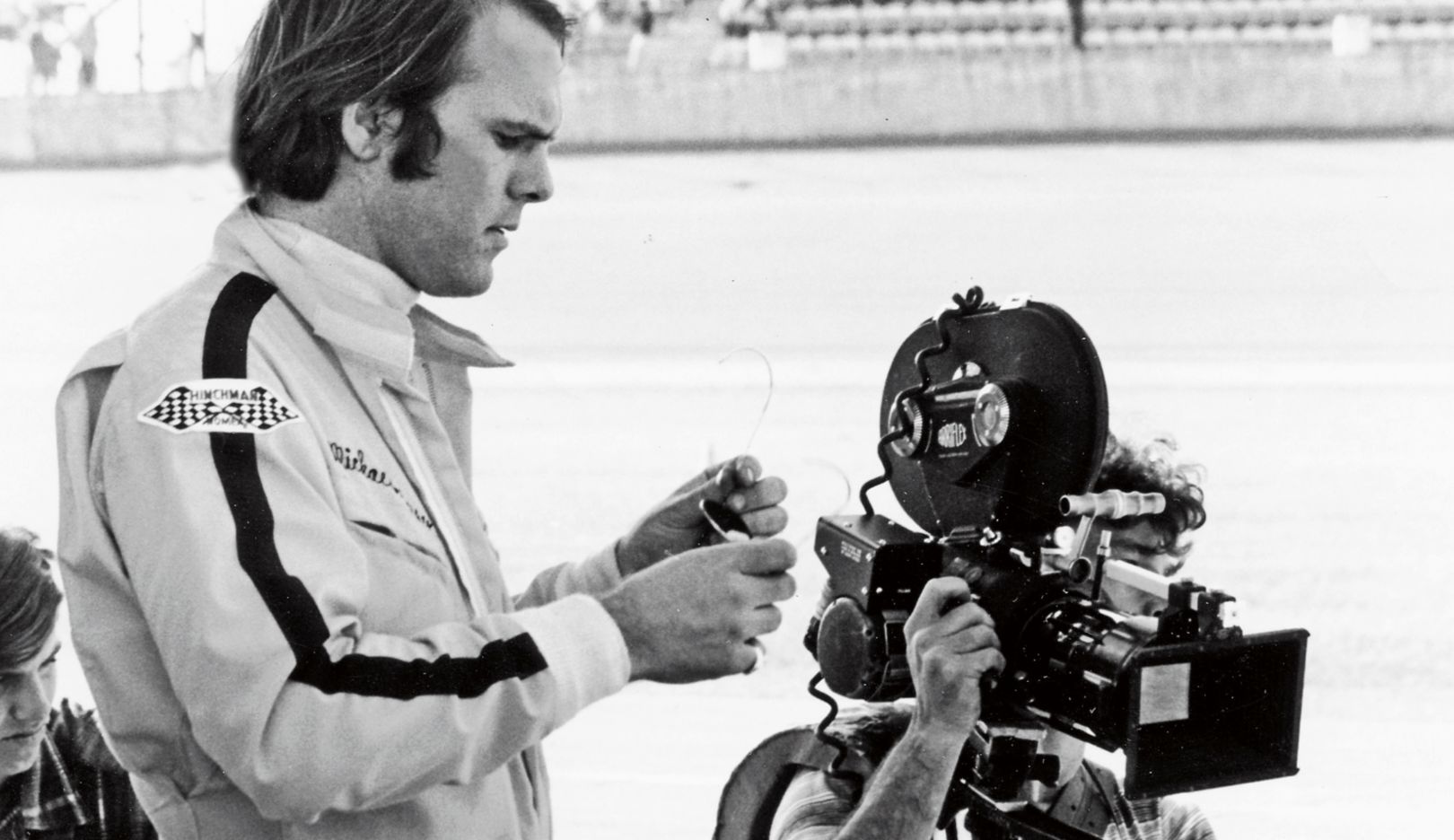

Michael Keyser—race-car driver, author, and producer—while filming in Sebring.Riveting nighttime footage was taken during a practice session, thanks in part to a 16-mm Bolex camera, specially installed in a steel frame on the rear. “We could press a button inside the car to turn each of the cameras on or off,” recalls Keyser. In contrast to how smoothly the filming was going, the paperwork for the race turned out to be nerve-racking. The Automobile Club de l’Ouest, the organizer of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, initially refused to admit the 911. But Barth, who speaks fluent French and could also call on the country’s racing community, found a loophole. “Fortunately, I was in contact with Louis Meznarie, a Porsche engine tuner I had met at rallies, and we could use his authorization—on the condition that we took his driver as the third member of our team.” Thanks to this trick, the newly declared French Porsche then sailed through the admission process in less than an hour and received start number 41.

During the race Keyser had an accident right before the Porsche pit, but the car suffered only minor damage. Although marked by the fray, the 911 finished in thirteenth place overall and won the GT class for engines of up to three liters. The fact that the car was the only Porsche 911 in the field to finish can also be traced to Barth’s foresight—he had ordered a short-stroke engine from Zuffenhausen especially for Le Mans. After the race Barth sent a letter to Porsche Board Chairman Ernst Fuhrmann describing his experience with the 264-hp test engine in detail. “We were a little slower than the 2.5-liter Porsches on the straights but were quicker out of the sharp curves. We drove the race with a maximum engine speed of 7,800 rpm.”

The early days

Jürgen Barth at the start of his racing career.Keyser and Barth went their separate ways after Le Mans. Two years would pass before Keyser completed The Speed Merchants. He cut around seventy hours of footage down to ninety-five minutes. With its impressive camera work and deep insights into the racing routines of stars like Mario Andretti, Vic Elford, Helmut Marko, Brian Redman, and Jacky Ickx, the movie is considered one of the classics of its genre.

Abandoned in a shed

Keyser sold the Porsche 911 ST 2.5 to Don Lindley in 1972 and bought a new RS model. Lindley drove the car in International Motor Sports Association races, the last one in Riverside in May of 1975. After changing hands twice more, the yellow 911 disappeared from sight—until 2008, when Marco Marinello, a Porsche connoisseur and president of Porsche Club Basel, heard reports of a potentially sensational barn find. A 911 ST 2.5 was said to be located in San Francisco. In 2013 Marinello and an interested Swiss buyer flew to California to determine the car’s identity. It was quickly revealed to be a real ST, albeit in miserable condition. But whether it was Keyser’s car was still unclear. It took an ad that Lindley had once placed in an automotive magazine, plus a purchasing contract signed by a third party, to achieve final confirmation one year later.

Rust removal and rebirth

With Marinello’s assistance, the Swiss buyer acquired the wreck and sent it to Porsche Classic’s restoration facility in Freiberg am Neckar. Porsche’s body experts were the first people to lay hands on the 911 to fix damage from several accidents that had bent the car out of shape. The car was missing its rear cross member along with its engine. The roof was caved in, apparently as the result of the unmanned car rolling down a bank and turning over. So the restoration crew straightened the shell on the alignment bench, removed all the rust and corrosion, and gave the car a new top and fender extensions. Two and a half years and more than a thousand hours of skilled manual labor later, it underwent cathodic dip-coating and was painted in the original code 117 color. In its characteristic bright yellow coat, the reborn ST was a star at the 2016 Techno Classica auto show in the German city of Essen. A successful comeback!